Forthcoming in Print, November 2022.

Introduction: Paradigm Shift and the Rejection of the Conventional View

Shifts in academic paradigms are rare. Still, it was not long ago that the values taken to govern the private law were thought to be distinct from the values governing taxation and transfer. This was thought to be true, although for different reasons, in both philosophical and economic accounts of private law. The question was, for example, whether the law of contract and tort is properly governed by the values of autonomy and corrective justice or by distributive concerns instead. The conventional, indeed, the nearly universal view of Rawlsianism—the overwhelmingly dominant theory of liberalism and distributive justice—was that the private law lies beyond the scope of Rawls’s two principles of justice.

Simply put, for Rawlsianism, the private law was not thought to be the province of distributive concerns. In more academic terms, the private law is not properly understood to be subject to Rawls’s range-limited principles of justice. In this conventional view, the private law is not part of what Rawls describes as “the basic structure of society,” which is roughly limited to basic constitutional liberties and taxation and transfer. This view invites the conclusion that Rawlsian political philosophy—despite its lexically ordered, distributive demand that economic institutions are to be arranged to the maximal benefit of the least well-off—is stunningly neutral with respect to the economic arrangements and ordering of the private law. This thinking led to the conclusion that the private law, if it is to exist, may be justified by values or principles other than Rawls’s lexically ordered principles of justice, whether wealth-maximization, autonomy, or pre-conceived or even pre-political notions of property entitlement.

At the same time, the dominant view in law and economics has been that the private law should be sanitized of egalitarian or equity-oriented values. The seductive idea was that any desired egalitarian moves could be achieved more efficiently through systems of income taxation and transfer than through any egalitarian alterations in private law rules. The conclusion was that the private law should be constructed to maximize wealth (e.g., optimal deterrence in tort), leaving equity-oriented demands for the system of income taxation and transfer. The argument’s invited conclusion was that any egalitarian (i.e., non-wealth-maximizing) adjustments to private law rules are inefficient, even if well-intentioned, private law constructions. If one conjoins the conclusions of both arguments, even a Rawlsian arguably ought to adopt the wealth maximizing conception of the private law.

Our early work, arguing against the conventional view, lead to a sustained analysis of this law and economics argument as well. We have argued that there is an “entitlement” flaw in both conventional approaches. Despite well-entrenched views on both sides, our objection has been well-received, and change is upon the legal academy. A wide range of scholars have begun to reject these two conventional views. But in our view, scholars have not always fully recognized what we take to be the full ramifications of the private law being constructed by distributive principles.

As we say, academic paradigm shifts are rare; being at the center of one is rarer still. We are honored that the Virginia Law Review has provided us an opportunity to continue the dialogue that proceeds at the heights of the legal academy. In what follows, we aim to discuss our position regarding Rawlsian private law while engaging with scholars who have further developed this complex debate. Ultimately, we hold that, despite the purported complications, there is, as we path-breakingly argue, a Rawlsian account of the private law.

For Rawls, the “basic structure” of society is understood to embody political and legal institutions that materially affect citizens’ life prospects, such as basic constitutional liberties, security of the person, the system of taxation and transfer, schooling, and fiscal policy. These institutions are taken to be subject to and governed by what Rawls famously calls “the two principles of justice.” However, significant scholarly controversy has arisen over the question of whether the private law (e.g., contract, tort, property, etc.) is properly understood to be within the basic structure of society.

The controversy over the question of the breadth of the basic structure is understandable: Rawls is believed to have been less than perfectly consistent. But, with regard to the specific relationship between the private law and the basic structure, we have argued that the historically conventional view—that private law is beyond the reach of the two principles of justice—must be mistaken.

It is important to understand what is at issue in this debate. It is neither a mere scholastic exercise, nor a simple game of words; significant matters of social and economic justice are at stake. Consider, for example, the so-called “causal” requirement in tort law—typically associated with the corrective justice conception. The idea here is that, from the perspective of a consequentialist approach, tort liability ought to be constrained: tort defendants are taken to be liable only for harm they have “caused” plaintiffs and they owe a duty of repair only to such plaintiffs. This “bilateral” or interpersonal relationship, although stated several ways, is central, for example, to backward-looking approaches to tort, even despite the contested status of the concept of causation.

While the causal requirement may be a necessary condition to a number of conceptions of justice, it can also serve as a significant impediment to otherwise seemingly just “systems” or distributive approaches to accident management. Consider for example, unjustified risk-taking, whether reckless or negligent. Such activity, absent an actualized harm, is insufficient to incurring tortious liability. So, ex ante accident management systems that focus on liability for unjustified risk imposition are objectionable for failing to satisfy the causal requirement. Still, ex ante liability, properly and narrowly assigned, is an important tool in the social planning and institutional design of accident management. It is useful, for example, in cost spreading and deterrence, both of which can be instrumental to achieving certain accounts of social justice.

Indeed, our own legal system regulates driving a motor vehicle not only with tort, but also with criminal law. The latter imposes liability for what might be termed risk imposition even in the absence of harm caused—for example, penalties for speeding, driving under the influence, and violating various other traffic laws. If tort law were to be subject to the goals of social planning and distributive justice, say, a special concern for the least well-off or people most likely to bear the cost of accidents, swaths of the causal requirement may need to be jettisoned. In addition to the traffic example, market share liability, where liability is predicated upon plaintiffs’ share of a market in faulty products, as opposed to causation, also might be a common approach to tort liability and accident management. While the imposition of liability in these instances fails to comport with the traditionalist causal requirement, it may be crucial to certain forms of accident management, whether conducive to advancing the position of the poor or creating optimal deterrence with the aim of wealth creation.

I. Distributivism and the Private Law

A. New Perspectives

The recent and overwhelming trend in the literature has been to concede, as we have long argued, that the private law, properly understood, is part of the basic structure. Yet important scholars seemingly hold that this dramatic change may not have the full implications for the private law’s substantive construction that one might expect. This is puzzling, given the Rawlsian stipulation that the basic structure defines the range-limitation of the two principles of justice. Indeed, one begins to wonder what the substantive difference is between a set of institutions being inside versus outside the basic structure, were the former not to entail them being subject to (i.e., governed by) the two principles of justice. The ultimate question is whether the two principles of justice would construct a substantive private law. Conceiving of the private law as inside the basic structure but not subject to the two principles of justice seems paradoxical. But scholars have worked to address the paradox. That is, they aim to construct strategies that purport to demonstrate the compatibility between Rawlsian distributive principles and values drawn from alternative accounts of the private law.

B. Conceptions of Distributivism

In the H.L.A. Hart Memorial Lecture, Samuel Scheffler, in a dramatic departure from the conventional view, has argued that the private law, for Rawls, must be located within the basic structure. He starts by rejecting the view that the private law might lie outside the basic structure, notably describing the historically conventional view as intellectually “feeble,” and asks what this conception entails for the private law’s substantive construction. Scheffler discusses several well-known possibilities. The first he terms “strong distributivism,” which provides that the private law “should be designed solely to serve the distributive purposes of the difference principle.” He correctly rejects this position, as we have, as it ignores the lexical priority of the first (liberty-oriented) principle of justice and equality of opportunity. Scheffler’s “strong distributivism” focuses exclusively upon economic distribution, the domain of the difference principle (requiring distributive shares to maximize the position of the least well-off). The Rawlsian position, however, is that the liberty and opportunity principles, taken in lexical priority, constrain the difference principle’s economic construction. The first principle of justice, for example, might play a significant role in providing for the security of the person in the construction of an accident reduction and compensation scheme. Presumably, however, the difference principle would nonetheless construct much of the private law, since a great deal of the private law is chiefly concerned with economic matters. This is what we have called the High Rawlsian position. Importantly, the first principle of justice is not robust in the construction of property, economic relations, or the structure of the market. It is silent regarding the details of ownership and entitlement—limiting itself to what Rawls describes as “personal property.”

The next possibility Scheffler calls “weak distributivism.” As he acknowledges, weak distributivism might appear to be an idiosyncratic, if not circular, possibility for Rawlsianism. The idea is this: first, a narrow, basic structure (the basic constitutional essentials and the system of tax and transfer) would be constructed to satisfy the demands of the two principles of justice, inclusive of the liberty principle and equality of opportunity. Then, one is free to add any private law construction that avoids worsening the position of the least well-off from the perspective of the baseline drawn by the initial construction.

Therefore, crucial to weak distributivism is that the selection of a conception of private law avoids “worsening the economic position of the least favoured members of society.” Constraining the range of the two principles of justice by excluding the private law from the initial construction and instead invoking the “not worsening test” is functionally equivalent to converting, solely for the private law, Rawls’s maximizing conception of the difference principle to a significantly weaker “sufficiency principle” analogous to the structure of the revised first principle of justice’s liberty construction. This initial move creates a normatively arbitrary baseline in the initial set-up, as it is inattentive to the economic entitlements created by the private law.

Still, the choice of private law might be said to be “in” the basic structure, as it is constrained by the “no worsening” condition. The upshot is that this constraint, once satisfied, would leave the private law not constructed by the Rawlsian principles of justice, allowing that it might be “fixed in other ways.” Scheffler recognizes that there is a baseline problem with respect to the “no worsening” constraint. In doing so, he aptly notes:

Suppose there is one way of designing contract law which, when the rest of the basic structure is properly designed, will maximise the position of the worst-off group. Relative to that baseline, any other way of designing contract law will worsen the position of the worst-off, and so any design that is non-optimal is ruled out. . . . And it is unclear why any other baseline would be appropriate.

Thus, the possibility exists that “weak distributivism” essentially collapses into strong distributivism. If this collapse can be somehow staved off, then ironically, weak distributivism, despite recognizing that private law is in the basic structure, may be in many ways analogous to the conventional view—which we and Scheffler reject—leaving Rawlsianism neutral with respect to a range of private law constructions.

Recognition of the baseline problem points to an even deeper concern. Weak distributivism contemplates the structure of contract and tort, without attention to the antecedent structure of the full range of property entitlements, which are fundamental to private law and are themselves a function, too, of taxation and transfer. Property, including the details of ownership and control, is itself unquestionably part of the basic structure and must be constructed according to the demands of the principles of justice. For this reason, there is a certain level of incoherence that runs through the position. Taxation and transfer require and define (respectively) entitlement baselines; these would include any rights to compensation, transfer, or exchange.

The conceptual distinction required by “weak distributivism” risks circularity. Given that private law defines and enforces entitlement baselines, the initial entitlement baseline cannot be constructed at the first step of the weak distributivist’s argument. The question of the basic structure is in no small measure the very question of economic entitlements; it would speak to the same thing. Importantly, the Rawlsian scheme is not concerned with traditional Anglo-American conceptions or doctrinal modules of the “private law” as a normative baseline. Rather, the focus is on the details of ownership and control, inclusive of personal security and transactions, governed by the two principles of justice defining who owns what and why and the details of such ownership. The weak distributivist compatibility strategy is unacceptable, given this incoherence.

In important and highly influential work, Arthur Ripstein, Samuel Freeman, and Gregory Keating have recently (re)addressed the relationship between Rawls and the private law and offered further accounts. While Ripstein’s view of the basic structure is contested, he has newly argued that the private law can remain conceptually independent of the two principles of justice. This is based on his commitment to the distinction between background justice—the domain of public law—which, for Ripstein, presupposes the idea of foreground justice, the domain of transactions. Samuel Freeman has argued, in agreement with us, that property, contracts, and much of tort law are within the basic structure, but he is skeptical of the role of the difference principle. Gregory Keating, too, has agreed that the private law is in the basic structure but holds that a form of empirical overlap may produce a form of non-principled compatibility. In what follows, we discuss these positions further.

In Private Wrongs, Arthur Ripstein aims to demonstrate compatibility between his largely backward-looking private law theory—fueled by comprehensive Kantian notions of freedom and responsibility—and Rawlsian justice. Here, Ripstein appears to sidestep questions concerning the breadth of the basic structure. But whether Ripstein holds that tort is inside or outside the basic structure, absent any stopping point akin to the “no worsening requirement” described by Scheffler, Ripstein’s private law construction is sufficiently independent of Rawls’s two principles of justice to render the distinction meaningless.

Ripstein distinguishes between background and foreground justice, where background justice is constituted by mandatory rules, constructed by the Rawlsian principles of justice, while foreground justice is the domain of the permissible voluntary or private sphere, governed by his preferred Kantian account of private law predicated on pre-institutional notions of freedom and responsibility. The purported demand for a private sphere, in Rawls, creates the needed space for compatibility. As interesting as this view is, it will not get Ripstein his independent “private” view of tort and contract. In the Rawlsian scheme, all such rules, whether constraint-imposing or liberty-allowing, are fixed constructions of the two principles of justice. Any underived distinction between background and foreground justice is off target; the principles of justice construct the very distinction in question. Such rules, then, cannot be altered in service to a “new” moralized conception of contract or tort. For Rawls, the same is true of the public/private distinction, which is not an underived starting place as may be found in other conceptions of liberalism, but instead the derived outcome of the construction. It would appear that Ripstein’s independent Kantian private law conception of tort and contract, derived from the re-introduction of “freedom” and “responsibility,” is not admissible at this stage. Such a (re)introduction would conflict with the Rawlsian construction, providing an alternative conception of the same.

In recent work, torts scholar Gregory Keating notes that significant areas of tort doctrine are distributive and welfare-oriented. He correctly recognizes that for Rawls, tort would be, contra the conventional view, “part of the basic structure, with its own distinctive role and concerns,” but importantly not walled off from the overall accident reduction scheme and not directly read off of the difference principle.

Keating, however, offers an (empirical) compatibilist possibility quite distinct from Ripstein’s approach. We agree with Keating’s rejection of the conventional view. But Keating may at points seem to be overly optimistic in discussing what might be even empirically compatible with a Rawlsian scheme as a matter of non-principled overlap. He remarks that the complete Rawlsian scheme of legal and political rules “is compatible with either enterprise responsibility schemes or the individual responsibility of ‘private law’ as Ripstein conceives it.”

The possibility of over-interpreting Keating looms large. Keating is addressing his argument to the possibility of empirical overlap in the construction of the ultimate scheme of legal rules, not to the principled commitment of the sort Ripstein offers. There is an important distinction to make here: Rawlsianism might construct a right for individuals to bring suit or demand recourse, but such a right would not be constructed for the Kantian reasons of freedom and responsibility.

The right would instead be derived from security of the person, equality of opportunity, and economic distributive reasons. More comprehensive or Kantian conceptions would be too focused on conceptual independence, derived from freedom and responsibility, to be required at this stage of Rawlsian argument. But Keating may be overly optimistic of even empirical overlap, which seems unlikely to be robust given the Rawlsian scheme’s lack of commitment, for example, to the causal requirement or to backward-looking, “corrective” remedies.

Consider further possibilities. In various parts of Liberalism and Distributive Justice, especially Chapter Five, “Private Law and Rawls’s Principles of Justice,” Rawls scholar Samuel Freeman provides an extensive discussion of Rawls and the private law. Freeman holds that the debate surrounding the narrowing of the basic structure owes to a mistake: an “infelicitous expression” on Rawls’s part. Freeman holds that the correct view of the basic structure is broad. He agrees that contract and tort law are within the basic structure and are subject to construction by the principles of justice. But Freeman is somewhat skeptical of the role that the difference principle might play in the construction of tort law, arguing that tort law is largely a first principle construction.

We too have extensively argued that a large part of Rawlsian accident management involves personal security as a first principle matter, but we also hold that a significant portion is an economic construction to be governed by the difference principle. We have called this the High Rawlsian position, consistent with the High Liberal position (ironically a term coined, as best we know, by Samuel Freeman). Freeman’s hesitance regarding the difference principle appears to derive from two main concerns: (1) an interpretation that such governance would result in decisions being “read off of” the difference principle in a direct (and unjust) manner, and (2) the idea that, for Freeman, torts are largely analogous to crimes; tort remedies are to respond to rights violations that should not have happened in the first instance, so they are (re)distributive, as opposed to distributive.

First, tort decisions, the very construction of the negligence standard, or the bounds of strict liability no more need to be “read-off” of the difference principle than do the rules of taxation. Tort law, and accident management more broadly, would find their home in an overall scheme that maximizes the position of the least well-off. That scheme is, of course, subject to the lexically prior liberty constraints governing security of the person. There is no commitment to any specific pre-ordained equity-oriented outcome. By analogy, the Rawlsian scheme would likely violate horizontal equity in taxation; there would be no antecedent commitment to a specified set of marginal income tax rates. The complete set of legal rules would be set in reference to the position of the least well-off. The selection ultimately is inter-schemic in order to best satisfy the requirements of the two principles of justice, not an intra-schemic reflection of equality as between individual people in rendering legal verdicts, whether in tort or taxation. Correspondingly, a poorer party surely need not necessarily prevail in civil litigation. The argument to the contrary is predicated on a misunderstanding.

Second, tort would provide security of the person consistent with sufficient liberty, but the difference principle would likely speak in part to the negligence standard; any selection between, for example, property and liability rule protection; the magnitude of honest industry; and importantly the question of who bears the cost of its attendant accidents (tragically, there always will be some). Further, tort helps define which externalities are to be internalized and which costs are to be associated with which activities. Much of this is distributive as opposed to redistributive or, contra Freeman, a backward-looking correction, setting initial baselines that will significantly affect the life-prospects of the least-well-off. Once sufficient basic liberty and opportunity are constructed, largely in terms of security of the person, the remainder would be subject to the difference principle, as opposed to, for example, notions of optimal deterrence as found in the economic analysis of law.

We will return to Freeman’s skepticism regarding the maximizing nature of the difference principle in Section III.B. But still, it is important to appreciate that the two principles of justice play different roles in what are traditionally considered different bodies of the private law, to the extent that they will invoke an economic construction. We noted above that the High Rawlsian position restricts the ability of the first principle of justice to construct any broad or robust economic entitlements. However, the first principle’s demand for security would necessitate a robust role in the accident reduction system. To the extent, for example, that the tort system provides for the delineation of risk and cost baselines pertaining to honest industry, both in protecting security of the person and maximizing the position of the least well-off, it would be constructed in service to the demands of the two principles of justice, in lexical priority.

II. Rawlsian Contractualism and the Private Law

Rawls offers a systems approach to legal and political institutions. One cannot simply construct the larger body of legal and political institutions without attention to the private law and then slip-in one’s preferred account of the substance of the private law. The introduction of a conceptually independent account of the private law will almost certainly upset the interworking of the system and its goals. For example, were a corrective justice-oriented account of tort to systematically and routinely require large payments from the least-well off to the better off due to negligence, it would violate the weak distributivist “no-worsening” condition.

Any rights of exchange (contract or gift), the system of accident reduction and compensation (tort), and taxation and transfer are, for Rawls, the very question of ownership, entitlement, and control. There is no pre-ordained commitment to traditional or doctrinal legal categories nor to a distinction between so-called “underlying” property rights and “transactional” rights, as might be found in some pre-institutional, doctrinal, Kantian, or Lockean accounts. Importantly, where a distributive maximand is in place, it is wholly indeterminate whether a rule imposing a fifty percent tax rate on income is to be described as a rule of tax, a rule of property, or a rule of contract.

Importantly, all entitlements need to be set in conjunction with an optimal tax rate associated with the specific maximand, the appropriately constrained difference principle. To do otherwise will create distortions from the perspective of the constrained difference principle that cannot, contra Kaplow and Shavell’s taxation and transfer thesis, simply be recuperated by adjustments in progressive marginal taxation rates without causing additional inefficiency deleterious to the position of the least well-off.

For Rawls, ownership and control are to be constructed jointly as part of the system of entitlements constructed by the two principles of justice. They are the derived outcomes of the institutional construction, not the result of a direct appeal to a free-standing or underived set of first principles. To think otherwise is to significantly under-appreciate the Rawlsian project’s ambition in its rejection of traditional or doctrinal details of property and ownership and control. Rawls is offering a legal construction or “replacement” theory which is taken to be just by virtue of its original position (“OP”) derivation.

The selected scheme of legal and political rules is suffused with the principles of justice; new or exogenous fairness or justice-oriented objections to the scheme are misplaced at this stage of the argument. Such objections, coherently raised, must be addressed to the derivation of distributive principles themselves or the Rawlsian assumptions that constructed them. It is in this sense that Rawlsianism is importantly distributive, as opposed to re-distributive. In our estimation, much of the worldwide allure and intellectual sensation surrounding Rawlsianism, for better or worse, owes to this very fact: the two principles of justice create afresh.

The principles of justice are addressed, at least, to legally enforceable interpersonal relationships. Were values associated with non-distributive conceptions of private law necessary to justice in the well-ordered society, representatives in the OP would have imposed such values upon the principles of justice themselves. To re-introduce such values at the stage of the legal construction would be to deviate from the very conception of justice derived in the OP.

True, the two principles of justice are not addressed to all normative matters, for example, aesthetic or romantic values. Still, it is important to note that the non-aesthetic aspects of, say, museum administration, such as endowment policy, taxation and nonprofit status, etc., would be regulated by the two principles of justice; so too would, by analogy, the non-academic, fiscal aspects of universities and the details of property ownership among life-partners, households, etc., during the pendency of their arrangements and in the context of separation or divorce. Even though Rawls’s two principles of justice do not speak to everything, the first principle of justice might be required to weigh-in on, say, a right to bequeath personal property, and would, too, constrain the difference principle in governing the tenets of religious doctrine within religious organizations as a matter of freedom of thought and conscience protected by the lexically prior first principle. The domain of non-applicability is quite narrow, indeed.

Current, conventional notions of marriage allow each partner a veto power, but do not require input from third-party stakeholders who might be affected (such as children, parents, and grandparents). A Rawlsian scheme would consider, although need not accept, the possibility of alternative arrangements in order to satisfy the demands of the two principles of justice. The structure of a legally binding ability to enter or exit civil commitments might be designed in service to the first principle of justice, while the second principle of justice might construct the conception of equality of opportunity and the economic nature of such relationships. But presumably some interpersonal dynamics of family or romantic life would remain open, as mandated by the first principle of justice. The same holds, by analogy, for the aesthetic evaluations necessary to a bona fide museum of fine art or the academic standards of a university.

The two principles of justice are forward-looking. The difference principle is maximizing a feature we discuss further in Part III, subject to lexically prior constraints of liberty and equality of opportunity. Given these features of Rawlsianism, there is little indeterminacy or non-mandated “openness” in the selected scheme of legal and political rules. In discussing institutional design, Rawls draws an analogy between the rules of taxation and contract law, holding that the operative bodies of both are part of background (i.e., distributive) justice and, therefore, subject to the principles of justice. Rawls arguably invokes notions of “simplicity” and “practicality,” consistent with the principles of justice, as a mere guidepost for institutional design, perhaps constructing rules that apply to end-state users: individual citizens. But if this is correct, despite all the controversy, it is not clear where “openness” sufficient to the construction of exogenous conceptions of private law might be found nor how an appeal to such demands might be motivated at this stage.

While it is true that the two principles of justice are range-limited, it is inconceivable to hold, as the conventional view once did, that the operative function of any private law construction should be understood as other than under the domain of the two principles of justice. Indeed, Scheffler describes it as intellectually feeble. This seems particularly clear if one considers the role such operative bodies of law would play in the provision of security of the person and in defining markets and the free and fair terms of cooperation and economic exchange.

Once the Rawlsian scheme of legal and political rules is selected, compatibility between Rawlsianism and non-distributive mandates concerning any “private law” construction seem ill-motivated. Further still, the re-introduction of such private law conceptions risks threatening the very framework Rawls set out to devise. The Rawlsian ideal is to construct a complete set of just legal and political institutions for the basic structure of society, acceptable even to property skeptics. Independent accounts of the private law are competing approaches often derived from a moralized account of the Anglo-American common law, as in the New Private Law Theory. As such, they speak to the same thing; they offer a competing conception of the very same concepts. Importantly, for Rawls there still may be constructed private law modules, representing, for example, innovation policy, accident management, commercial reliance, etc., but these modules need not pattern our conventional doctrinal law of intellectual property, tort, or contract, respectively.

Return now to the question of compatibility with traditional private law or ex post private law conceptions. The problem, as we see it, runs even deeper still. The Rawlsian OP-derived construction is robust. For Rawls, “justice” is the sector of the concept of “right” that encompasses prominent social, political, and legal institutions. Importantly, even the social institution of promising and promise keeping is governed by the OP-derived two principles of justice.

Further, it is not only the conception of justice that is OP-derived for Rawls. Any remaining sectors of the concept of “right,” we are told, “are . . . relatively few in number and have a determinate relation to each other.” It is true that we are neither told what the sectors of rightness might be, nor are we given the content of the principles for each sector. But we are, importantly, given the procedure by which they are to be derived, the OP. So, the ultimate construction is conceived of as “rightness as fairness.” It seems unlikely that any such OP derived principles would magically construct Anglo-American private law or have space for something much akin to it. Rawls himself lists as candidates, OP-derived, “principles for individuals,” and “the law of nations.” Once one adds those to the principles for institutions, it is hard to imagine what might be left.

Rawls discusses principles for individuals, inclusive of the OP-derived “natural duties.” But for Rawls, the natural duties are not natural in the ordinary sense of the term—they are not exogenous of the OP-construction. So, both the principles that apply to individuals and those that apply to social institutions are OP-derived constructions. As such, they serve as a “replacement” for an ordinary language account of the normative concepts in question. And to avoid conflict, the two sets of principles, those that apply to institutions and to individuals, operate in conjunction and must not conflict, which explains the demand for the complete OP derivation. The principles of justice, those for institutions, are required first to set needed baselines without which notions of “harm” or “obligation,” for example, would be incoherent or lack normative force.

Given the demands of the OP-derived two principles of justice and the OP-derived principles that apply to individuals, it is not at all clear where (conflicting) ordinary normative notions might fit and even more importantly, why they would be needed in a theory of this kind. The Rawlsian OP construction imposes all necessary justice-oriented requirements upon the principles of justice, which in turn construct legal institutions. Any appeal to “everyday” or pre-institutional normative values or the Anglo-American common law itself is ill at home with the mandates of the Rawlsian construction. Importantly, common law doctrine or moralized accounts cannot serve as the normative baseline. While it is true that the Rawlsian system does ultimately admit of reflective equilibrium, this does not open the floodgates to insert antecedently desired moralized legal or political modules.

Consider, as an instructive example, how private law might construct the role of gift-giving in a Rawlsian system. It could be quite constrained. There is no guarantee that, post-institutionally, persons would be “free” to act in accord with (pre-institutional) notions of beneficence. Gift-giving could upset entitlements as defined and implemented by the two principles of justice. Such transfers could be closed in certain settings as a direct matter; for example, it might be instrumental to the scheme to limit or eliminate donor influence at charities. In addition, gift-giving might be taxed. This might include taxation of the donor, the recipient, or both and need not pattern the current U.S. tax code or the “Duberstein test.” This tax rate could equal or even exceed 100%, perhaps on the notion that the donor gains “sway” or “sycophant appeal” while losing some welfare, while the recipient, at the same time, gains welfare. Or, if progressive taxation were instrumental to the scheme, it would be unlikely that donors in an intra-familial setting be allowed a deduction, lest high-earners be able to “level down” their incomes through donations to lower-income family members.

Now, consider the role of “openness” in a Rawlsian system. Rawlsian entitlements might instrumentally construct some space in which individuals would govern (post-institutional) liberty to transact voluntarily. Such openness would be mandatory. As such, it could not be reconstructed by the demands of an alternative theory, say, Friedian contract law. Further, such alternative conceptions of contract law would not be deployable as warrant for broadening the openness in the Rawlsian system. The boundaries of openness are determined by the two principles of justice; any demands for a distinct range of openness derived from an alternative theory of contract would conflict.

III. The Possibility of Incompleteness: Scheffler’s Lacunae Hypothesis

While Scheffler agrees that the “private law” is properly understood to be within the basic structure, he raises the hypothetical possibility that distributive principles may be insufficient to fully construct an acceptable system of private law. The hypothesis is that there are aspects of a sufficiently satisfactory private law, and perhaps criminal law, that are just not about distributive justice. This hypothetical insufficiency would provide a demand for the operation of additional non-distributivist principles to construct the aspects of private law. As Scheffler points out, notably similar lines of questioning can be found in important work by both John Goldberg and Seana Shiffrin. But Goldberg and Shiffrin are non-Rawlsians and offer theories quite distinct from Rawls. Still, the issue is this: What if additional principles, drawn from the concept of justice, are needed for a satisfactory private law construction—values whose principles we have not been given by Rawls?

Yet recall that the OP-derived principles of justice construct the private law as a function of the objective index of the primary goods, with attention to the social value of self-respect, in contrast to utilitarianism. This alone would go a great distance to slow the line of questioning, were the concern that Rawsianism may bear some of utilitarianisms’ alleged shortcomings surrounding, say, a purportedly impoverished account of promise keeping. Where exactly might the insufficiency lie? The Rawlsian OP, itself, is the “modeled” conclusion to a complex foundationally deontic argument predicated upon underived, pre-theoretic notions of human (a.) freedom and rationality and (b.) equality. Then, consider the OP-derived two principles of justice that provide a constructed account of (c.) balanced basic liberty, (d.) equality of opportunity, (e.) equality and efficiency in economic relations, (f.) the lexical ordering among them, and their implementation measured in terms of (g.) the objective index of the primary goods. It is difficult to imagine what more is needed qua a theory of justice of this kind, particularly with respect to the purported incompleteness of legal institutions.

One is always free to raise high-order objections, whether to the two principles of justice as an incomplete or objectionable OP-derivation or object to the OP itself. But a danger of the skeptical line of questioning regarding “insufficiency” is that it may encourage getting things backward. The substance of Anglo-American private law is neither primitive nor the correct normative baseline for Rawlsianism. Private law constructions are the outcome of inter-schemic comparisons among complete schemes of legal and political institutions.

But Scheffler poses the higher-order concern:

If private law belongs to the basic structure, and if the role of principles of justice is to regulate the basic structure, and if principles of distributive justice . . . do not suffice to regulate private law, then there must be some other principles that regulate private law, and they too must be principles of justice for the basic structure.

Scheffler’s hypothetical concern is that Rawls has been silent on this issue, and if there were a need for such additional principles, such silence leaves lacunae in the Rawlsian system. But Scheffler’s suggestion is that such hypothetical lacunae would derive, not from openness in the maximizing system as others have held, but from a potential conceptual incompleteness in Rawlsianism. That is, the possibility that distributive justice is not sufficient to construct a satisfactory conception of the private law.

For Scheffler, rectifying any hypothetical incompleteness would require additional principles and an account of how they are to function consistently among the existing principles of justice. But were there such a need, Rawls has been silent. As Scheffler recognizes, “we have not been told what [they] are.” But, still, we have been told quite a lot—against a backdrop of Rawls’s property-skepticism—about the justice-suffused principles of justice that, in the alternative, would govern the private law. If one finds the resulting scheme unsatisfactorily incomplete, that is, containing lacunae, that would be grounds for turning to another, non-Rawlsian approach to the private law, likely one grounded in pre-institutional principles of property entitlement.

But were Rawls’s silence, in fact, revelatory of incompleteness—as opposed to the more obvious explanation, a lack of necessity—we have been given the procedure by which principles are to be constructed, namely the OP. Whatever the content of the as yet non-existent principles, it is unlikely that additional principles that would construct conventional, doctrinal, or ex post conceptions of the private law would survive the OP and be consistent with what exists. Constructing additional principles that (1) do not conflict with what we have, such that they (2) do not simply provide a competing account of the same is a difficult needle to thread.

Consider just how difficult it would be: the creation of a sector of justice, distinct from the domain of the two principles of justice, which are taken to cover security of the person in terms of liberty, equality of opportunity, and the construction of economic relations. True, an additional principle, lexically ordered, is conceivable; perhaps a principle imposing something akin to “choice sensitivity,” “responsibility,” “voluntarism,” or even expansive “private ownership.” But such a principle, specifically addressing private ordering of, for example, the account of private property rights, the primacy of the outcomes of consensual exchange, rights to exclude, contract, etc., would likely be either (1) addressed to the same subject as the difference principle and inevitably create conflict, or (2) require a very stringent lexical ordering to avoid conflict. Rawls has not always been so stringent in lexical ordering, shifting away from the liberty principle as maximizing to a sufficiency principle, significantly hampering the difference principle’s domain. But adding such new constraints to the scheme would inevitably lower the provision of primary goods to the least well-off. Such hampering may potentially even create a class of the “justifiably poor,” if the difference principle’s lexical subordination were to prevent the “grossing up” of shares that were reduced in service to the new, antecedent principle(s). The possibility of a shipwreck would appear to loom large. While tinkering with the Rawlsian system is worth considering, as one should not be driven to Rawlsian fundamentalism, this approach does seem to be striking out in a rather non-Rawlsian direction.

Still, it is true that Rawls writes of “free” and “fair” markets, at least once noting that “straightaway” we need an account of what “free” and “fair” mean. But do we have reason to doubt these terms would be constructions of the two principles of justice? The principles provide an account of the very same. Here, Rawls is responding to the “free market” or Lockean argument associated with Robert Nozick. It would be unusual if Rawls had intended an account of “free” and “fair” other than one derived from the two principles of justice. It would be further surprising if Rawls had offered a more Lockean approach to the “market” than the conception constructed by the two principles of justice in one of Rawls’s few responses to Nozick.

But Scheffler is clear that his suggestion of incompleteness is merely hypothetical. He leaves open the possibility that Rawls has given us enough for a theory of this kind and more specifically enough to know that Rawlsianism, would, on this account, be in principled conflict with independent conceptions of the private law, e.g., the corrective justice conception of tort or the will theory of contracts. It is unclear that we have been betrayed by silence.

In their recent and stimulating book on tort doctrine and civil recourse, Recognizing Wrongs, John Goldberg and Benjamin Zipursky touch on Scheffler’s H.L.A. Hart lecture. They interpret Scheffler and Rawls as requiring that an account of justice must have “something to say about the law of torts” and agreeing that private law would properly be understood as within the Rawlsian basic structure. While we agree (1) that the private law is within the basic structure, contra the conventional view, and (2) that it seems inevitable that the Rawlsian scheme would need to manage accidents, we caution, again, that this need not entail critical formal features of Anglo-American tort law. Rawlsianism would seem to require an accident management system, but not necessarily conventional “tort law;” recall Keating’s instructive remarks on, for example, the New Zealand accident scheme.

But Goldberg & Zipursky are doctrinal in their approach to tort law. We agree that the ultimate Rawlsian scheme would likely provide individuals an avenue for redress, which may even be basic in the Rawlsian sense as a matter of security of the person, but the structure and form that avenue might take remains to be determined by the two principles of justice. While it is true that accounts associated with the “New Private Law Theory” may have a connection to justice in ordinary parlance, this is not the Rawlsian conception.

For Rawls, absent the sort of OP-derived revision Scheffler hypothesizes, the Rawlsian scheme would have to make do with liberty, equality of opportunity, and economic equality in the construction of tort rules. Out of fairness to Rawls, this does go a good deal further than the ordinary language use of the term “distributive justice,” typically limited to the economic distribution. Given Rawls’s more expansive account, it is not clear that distributive justice would need to be given lexical priority over other forms of justice in ordinary parlance.

IV. Reciprocity, Fair Terms of Cooperation, and the Difference Principle

From the broadest perspective, the two principles of justice represent the normative value of what Rawls describes as “reciprocity,” or what can be described in lay terms as the fair terms of social cooperation. The “difference principle,” maximizing the position of the least well-off, constructs the economic aspects of the complete scheme of legal and political rules.

Here, one might draw a distinction between post-institutional entitlement and the more universal pre-political value of human equality and worth. For Rawls, the concepts of entitlement and ownership are constructed by legal and political rules, instrumentally in service to the two principles of justice. Deep notions of freedom and equality for Rawls are universal, or pre-political; they lie behind the construction of the OP and, correspondingly, the derivation of two principles of justice.

A. The Rawlsian Systems Approach

The relationship between the two principles of justice and Rawls’s views concerning the value of reciprocity has caused, in our view, undue disagreement in the literature. The disagreement has called into question whether Rawlsianism is best understood as a maximizing theory and may disguise how it is best distinguished from welfarism.

The Rawlsian aim is to produce a “systems” theory in contrast with what he takes to be the distributively flawed utilitarian or welfarist approach to the evaluation of social institutions. Rawls distinguishes his approach from the welfarist approach associated with utilitarianism or the economic analysis of law. Importantly, Rawls’s two principles of justice bear a maximizing component, which is, as we say, taken in lexical priority and does not aggregate value, in the same manner one finds in utilitarianism or law and economics.

Further, Rawlsianism ranks institutions according to their provision of an objective index of primary goods, as opposed to welfarism or wealth-maximization, which measure value in subjective “preference fulfillment” or monetary terms, respectively. In distinguishing his conception of distributive justice from utilitarianism, Rawls points out that the two principles of justice represent the abstract ideal of “reciprocity” or the “fair terms of cooperation,” as distinct from objectionable aggregating theories.

From these observations, however, it does not follow that the difference principle, over its proper range of application, is not correctly understood as a maximizing principle. Instead, the difference principle is best understood as a domain-specific maximizing principle which embodies a component of the complete conception of reciprocity, in conjunction with lexically prior values. That is, the difference principle sets the economic baselines required for a coherent evaluation of the fair terms of cooperation. The difference principle is not a proxy for the value of social reciprocity, rather, the difference principle is a component of the two principles of justice that concretely define the value of reciprocity or, in ordinary language, the fair terms of cooperation. In our view, the maximizing nature of the difference principle seals in the conception of justice, rendering the system impervious to alternative conceptions. It sucks the air out of the metaphorical room.

B. Freeman and Conceptions of Economic Reciprocity

Given the role that “maximizing” plays in our account, we address the suggestion that the difference principle may not be best understood as a maximizing principle. In what follows, we (1) discuss Samuel Freeman’s important claims that the difference principle may be best understood, in the first instance, as a non-maximizing (potentially) intra-schemic relational principle. We then discuss (2) the role of the primary goods, as opposed to wealth or subjective preference fulfillment, as the correct metric for evaluating private law constructions, and the lexical priority of liberty and opportunity over the difference principle, and finally (3) what we take to be the correct Rawlsian view of “reciprocity” or the fair terms of cooperation.

In recent and important work, Samuel Freeman has discussed the Rawlsian difference principle and the idea of reciprocity. For Freeman, the difference principle is not to be understood as imposing a maximizing demand, but instead as the expression of the value of reciprocity or the fair terms of cooperation. But Freeman analyzes the idea of reciprocity somewhat in isolation and appears to (re)evaluate it separately from (1) the lexically prior liberty and opportunity constraints of the two principles of justice and (2) the set of institutional rules and entitlements that ultimately instantiate the very conception of reciprocity in concrete terms.

Our concern derives from the idea that Freeman may be reintroducing a new conception of reciprocity addressed to the wrong level. The abstract conception of reciprocity must ultimately impose specific substantive constraints on legal institutions or construct finite or specific legal rules via the two principles of justice. Freeman proposes a conception of the difference principle as an intra-schemic “relational” principle, as opposed to a maximizing one. In his estimation, this conception better instantiates a conception of reciprocity.

Freeman, in contrast to our view, holding that Rawls views the difference principle itself as a principle of reciprocity, goes on to argue that this implies that the difference principle is non-consequentialist and non-maximizing. Freeman argues that “the justice of distributions to the least advantaged [is] decided by how well off they are compared with the most advantaged.” That is, the difference principle is an intra-schemic relational principle. But can this be right? True, Rawls is concerned with reciprocity, but notions of reciprocity are partially embedded in the (maximizing) difference principle itself. In other words, for Rawlsianism, the two principles of justice define the fair and just (or free and fair); they are suffused with the notion of reciprocity. Reciprocity is not to be reduced to the difference principle nor reintroduced as a separate intra-schemic, relational notion at the level of applying the difference principle. In our view, intra-schemic reciprocity is a derived outcome of the inter-schemic selection, not a starting place.

In rejecting the maximizing conception of the difference principle, Freeman provides an example of a society with a minimum share of $40,000. The possibility of achieving a $42,000 minimum share exists but should be rejected if it were to entail “substantial inequalities that are unjust.” Consider, perhaps, that the $42,000 minimum scheme contains considerably more billionaires than the $40,000 scheme. Yet concerns about that would seem to have been solved by the difference principle, properly understood and applied. We are evaluating shares in primary goods, not dollars. The former includes the social value of self-respect.

Freeman is correct that the (narrow) monetary package component of the (more robust) total package of primary goods received by the least well-off may expand or contract as between competing schemes of (selected) legal and political institutions. So, for the economist measuring solely in dollars, true, the Rawlsian scheme appears to be non-maximizing. But the difference principle is maximizing, subject to prior lexical constraints, in terms of the position of the least well-off in the total provision of primary goods.

By analogy, given that primary goods include security of the person, the Rawlsian difference principle would move away from an aggregating utilitarian scheme, in favor of a scheme with a greater demand for personal security. Given that one is maximizing in terms of primary goods, as opposed to dollars, security would not be completely traded away in favor of purely monetary shares. Presumably this would shrink the monetary component of the primary goods package available to members of the class of the least well-off. For example, the Rawlsian scheme might include more personal security, but smaller monetary shares, than the utilitarian scheme. Again, the two principles of justice—evaluated in terms of their provision of primary goods—provide, for Rawls, the account of reciprocity between persons and the fair terms of cooperation. Freeman here aims to (re)impose an alternative conception of equality (i.e., lower income disparity) than the two principles of justice would allow, while at the same time limiting the conception of reciprocity to the difference principle.

Freeman’s intra-schemic concern seems reminiscent of an objection to Rawls from the perspective of a more aggressive form of egalitarianism; namely, G.A. Cohen’s critique of the difference principle. That is, that the difference principle’s maximizing demands are objectionable, given Cohen’s commitment to a lower quantum of income disparity within the selected scheme. It is hard to see how representatives in the OP, maximizing self-interest and precluded from reasoning from envy or comprehensive doctrine, might have grounds to object to the maximizing conception of the difference principle. Rawls is, after all, a liberal whose chief goal is a sustained critique of the distributive flaws in utilitarianism. He is not independently committed to an intra-schemic relational conception of egalitarianism.

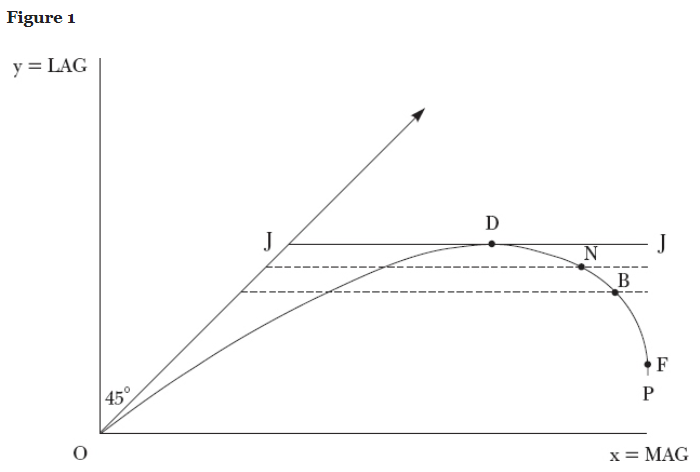

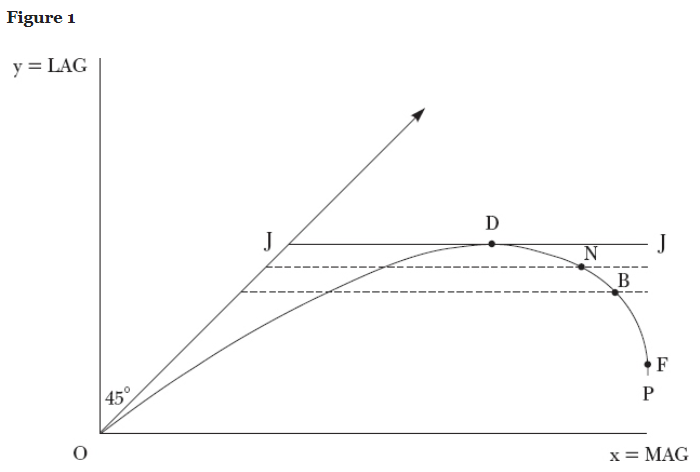

Consider the chart Rawls provides on page sixty-two of Justice as Fairness: A Restatement:

The y-axis is the least advantaged group; x, the most advantaged group; D represents the difference principle; N, the Nash point; B is Benthamite utilitarianism; F is feudalism and the J-J line is the highest equal justice point touched by the D. Here, Rawls is clearly aiming at maximizing the position of the least well-off (see point D) and demonstrating how this involves some sacrifice by the most advantaged group (cf. point B), while maximizing the position of the least advantaged group.

It is important to note that the chart compares the optimal application of alternative distributive principles. Rawls, for expository purposes, is comparing principles bearing differing axiologies (i.e., value systems) in order to amalgamate these principles on a single chart. But one must take care not to over-interpret the significance of the reductionist comparison for purposes of understanding whether the difference principle is maximizing. Rawls clearly interprets the difference principle as maximizing the position of the least advantaged group on the y-axis.

The upshot is that while Rawlsianism does not invoke maximization regarding monetary shares—in this Freeman would be absolutely correct—the theory is, nevertheless, maximizing. Once sufficient basic liberty, in respect of the two moral powers, and equality of opportunity are established, the correct comparison is among competing sets of institutions in their capacity to maximize the position of the least well-off. While this is not the account typically found in the economic analysis of law, it is nevertheless a maximizing and consequentialist theory, if a constrained one. A commitment to any independent or newly advanced intra-schemic relational conception of economic equality would appear unmotivated, given the full Rawlsian conception of reciprocity. This, too, is not merely a scholastic exercise. Interpreting Rawls as other than maximizing in making the final inter-schemic selection among completing sets of legal and political rules would, in our view, upset the (derived) account of intra-schemic reciprocity that owes to the selection itself.

Conclusion

There has been a welcome academic shift in perspective with regard to Rawls and the private law. This shift points to the conclusion that despite decades of international debate, there is a Rawlsian account of the private law satisfactory to contractualist theory of its kind. If we are correct, this account conflicts with important aspects of alternative approaches to private law, theoretical and doctrinal. Whether the Rawlsian account is fully satisfactory to those committed to alternative approaches is an open question; but if not, that is, in our view, a question that should be addressed to the acceptability of Rawlsianism itself.