Introduction

This Essay reports the first comprehensive network analysis of legal scholars connected through co-authorship. If legal scholarship was ever a solitary activity, it certainly is not any longer. Co-authorship has become increasingly common over time, and scholarship is now mostly a collaborative endeavor.1 1.See infra Figure 1.Show More These collaborations are important for both scholars and for scholarship, and so understanding patterns of co-authorship is crucial for understanding how legal academia functions as a market for intellectual labor and for the product of that labor: legal scholarship.

The labor market for law professors functions in many respects like other markets for skilled labor, and scholarly collaboration creates several channels for professional advancement. Co-authorship can result in greater scholarly productivity,2 2.See infra Part I.Show More and social networks formed through co-authorship may provide information channels for scholars to learn about hiring opportunities at other schools and for those schools to collect first-hand information about a prospective hire’s value to the law school community. In these ways, co-authorship can help a scholar’s promotion, compensation, and lateral mobility.

But as social networks tend to reflect within-group affinities—along dimensions of race, gender, and class, for example—they may have disparate impacts on the career opportunities of legal scholars. And the differences generated by social networks may exacerbate any inequalities that led to the original underrepresentation of certain groups. For example, recent evidence indicates that female economists collaborate less often and generally within smaller networks than men and that this difference in co-authorship networks explains 18% of the gender research output gap.3 3.Lorenzo Ductor, Sanjeev Goyal & Anja Prummer, Gender and Collaboration, Rev. Econ. & Statistics 24–25 (2021), https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_01113 [https://perma.cc/PS4Z-KXAK].Show More

Beyond the interests of the professoriate and law schools themselves, there are consumers of legal scholarship. For these consumers, patterns of co-authorship matter for how they affect the substance of legal scholarship itself. These consumers include judges, legal practitioners, government officials, journalists, and law students. Law students are sometimes direct consumers of legal scholarship, but they are also frequently indirect consumers through the influence of legal scholarship on classroom pedagogy. Legal scholarship influences the views law professors express in the classroom, and it influences the content of course materials, such as law casebooks.4 4.In some cases, law school texts are based on methodological approaches that have been developed as legal scholarship. See, e.g., Robert Cooter & Thomas Ulen, Introduction to Law and Economics (5th ed. 2007).Show More

In this context, the factors affecting co-authorship relationships influence the process and outputs of knowledge production and the training of lawyers. The contours of the co-authorship network will affect which scholars influence the trajectory of legal scholarship and what gets taught in the classroom, whether scholarship reflects diverse viewpoints and methodological approaches, whether insights and methods migrate between areas of study, which areas of legal scholarship are active and which grow stale. Thus, the composition of the law professoriate and the legal scholarship it produces are partly a product of the network of legal scholars. The history of legal academia can be partly told in these terms, and the future of law and legal scholarship depends on the evolutionary path of that network.

Research on co-authorship in law has focused on the claim that legal scholarship is more frequently solo-authored compared with other disciplines.5 5.Tracey E. George & Chris Guthrie, Joining Forces: The Role of Collaboration in the Development of Legal Thought, 52 J. Legal Educ. 559, 561–568 (2002); Michael I. Meyerson, Law School Culture and the Lost Art of Collaboration: Why Don’t Law Professors Play Well with Others?, 93 Neb. L. Rev. 547, 548–549 (2014).Show More Professors Ginsburg and Miles documented an increase in the number of co-authored articles from 2000-2010, which they attribute to the emergence of empirical legal studies.6 6.Tom Ginsburg & Thomas J. Miles, Empiricism and the Rising Incidence of Coauthorship in Law, 2011 U. Ill. L. Rev. 1785, 1800–1812 (2011).Show More A little over ten years ago, Professors Edelman and George considered the network of legal co-authorship.7 7.Paul H. Edelman & Tracey E. George, Six Degrees of Cass Sunstein, 11 Green Bag 2d 19, 22–31 (2007).Show More But because there was no database available at the time suitable for computational network analysis, they focused only on identifying the one legal scholar—Cass Sunstein—who they placed at the center of the web of legal co-authorship relationships.8 8.Id. at 27–30.Show More It is only with the recent availability of large amounts of digitized text data that computational network analyses of legal scholarship has become possible. In general, computational social network analysis is only beginning to get a foothold in legal scholarship, and work on the connectedness of legal scholars is limited.9 9.See, e.g., Daniel Martin Katz, Joshua R. Gubler, Jon Zelner, Michael J. Bommarito II, Eric Provins, & Eitan Ingall, Reproduction of Hierarchy? A Social Network Analysis of the American Law Professoriate, 61 J. Legal Educ. 76 (2011) (discussing the network of legal scholars and its impact on legal developments); Milan Markovic, The Law Professor Pipeline, 92 Temp. L. Rev. 813 (2019) (exploring how professors’ intellectual and social networks relate to the advancement of their careers); Keerthana Nunna, W. Nicholson Price II & Jonathan Tietz, Hierarchy, Race & Gender in Legal Scholarly Networks, 75 Stan. L. Rev. (forthcoming 2023) (analyzing how hierarchy, race, and gender affect the acknowledgment sections of law review articles).Show More In this Essay, I report the first comprehensive evidence of co-authorship patterns and the network of legal scholars.

I explore how the network of legal scholars and patterns of co-authorship evolved from 1980–2020. I document dramatic growth in the network of legal scholars, and a much greater increase in co-authorship, such that the legal academy can be described as a “small world” that has become smaller over time. Legal scholars are a more diverse group than they were in the 1980s, and although legal scholars tend to coauthor with other scholars of the same gender and minority status, this tendency has declined over time.10 10.See infra Part IV.Show More There is also evidence legal scholars are increasingly finding coauthors outside their own institutions. Finally, I examine the ordering of authors’ names on coauthored papers. Many law journals have recently changed their citation convention for articles with more than two authors. Rather than listing only the first author’s name followed by “et al.”, they will include all the authors’ names in the first citation to the work. A concern with the “et al.” convention was the possibility that underrepresented members in the legal academy were less likely to be listed as the first author on co-authored papers, leading to underappreciation of their scholarly contributions. The evidence for this concern is mixed. I find that racial minorities make up a greater share of first authors on such articles than their proportion of authors overall. By contrast, women and lesbian, gay, and bisexual (“LGB”)11 11.“LGB” is used instead of “LGBT” because the American Association of Law Schools (AALS) Directory of Law Teachers does not include data on transgender faculty.Show More scholars make up a lower share of first authors than their proportion of authors overall.

I. Scholarly Collaboration

Legal scholarship is not a solitary enterprise and professional colleagues intervene at various stages of the writing process. At the very start, informal conversations with other professors can help a scholar identify a project that is both tractable and makes a novel contribution. Once a project is far enough along, it will often be shared with colleagues within the scholar’s home institution for feedback and then presented at seminars or at national or regional conferences. Presentations of this sort allow the author to publicize and receive feedback that improves the work.

Scholarly norms in legal academia make it possible to trace many of the contributions made by one scholar to another’s work. The most obvious norm is citation for crediting related work and identifying authorities for propositions. Recent work by Keerthana Nunna, Nicholson Price II, and Jonathan Tietz excavates the “acknowledgement” footnotes that typically appear on the first page of law review articles.12 12.Nunna et al., supra note 9.Show More The footnotes reveal some of the less formal ways that legal scholars engage in knowledge co-production, and they provide a rich picture of a collaborative network among law professors, as well as the ways that hierarchy, race and gender influence who is acknowledged for their contributions to written work.13 13.Id. at 46.Show More

In this Essay, my focus is on co-authorship. Although citations, acknowledgements, and co-authorship are similar insofar as they all represent linkages between scholars that facilitate knowledge transmission, the co-authorship network is different. Most obviously, for citations and acknowledgements, scholarly influence runs in only one direction. And one doesn’t need permission to cite another author or acknowledge their contributions. As a result, the linkage reflects only the decision-making priorities of one party. By contrast, both scholars must agree to work together on a co-authored project.

Second, citations and acknowledgments are weak linkages between scholars. There may be no personal relationship between the citing and the cited authors at all. And the relationship between acknowledging and acknowledged scholars may amount to nothing more than an email exchange or a brief conversation. By contrast, in most cases, co-authorship will entail a long period—months or even years—of correspondence, conversation, and negotiation over a joint project. It is more likely co-authors will have an intellectual influence on each other. And the thickness of the relationship may create a channel for learning about each author’s personality, talents, circumstances, and ambitions, as well as sharing information about career opportunities at their institutions or in legal academia more generally. All of this can facilitate professional advancement.14 14.On the importance of networks in job matching, see Yannis M. Ioannides & Linda Datcher Loury, Job Information Networks, Neighborhood Effects, and Inequality, 42 J. Econ. Literature 1056, 1061–1062 (2004).Show More

Given the commitment that co-authorship entails, scholars do not enter co-authorship relationships lightly. Why do legal scholars co-author? Professors Ginsburg and Miles offer several reasons.15 15.Ginsburg & Miles, supra note 6, at 1788–90, 1794. For a theoretical model of the co-authorship choice, see Bruna Bruno, Economics of Co-authorship, 44 Econ. Analysis & Pol’y 212 (2014).Show More First, scholars may have complementarities in skills or expertise that allow them to make contributions together that that they couldn’t on their own. A related benefit of co-authorship comes from specialization. Even if two scholars have overlapping expertise, they may be able to write an article more efficiently by specializing their contributions. A second set of reasons relate to professional esteem. Coauthoring with other scholars allows an author to both increase her research output and diversify her scholarship by making contributions outside of her primary area of expertise, all of which will generally increase her professional profile.16 16.Id.Show More An important caveat to this is that co-authors may receive unequal credit. For example, there is evidence that female economists are penalized for coauthoring while male economists are not.17 17.Heather Sarsons, Recognition for Group Work: Gender Differences in Academia, 107 Am. Econ. Rev. 141, 144 (2017).Show More

Of course, there are also costs of co-authorship. Co-authors must agree about the substance of their piece and about the style of writing. They must be content in their working relationship, with the timing of the project, with the process of exchanging drafts and editing, and with spending hours together in conversation. And they must work out the assignment of responsibility and credit for the project, including how their contributions will be recognized through the order of their names on the final paper.18 18.Ginsburg & Miles, supra note 6, at 1790–93.Show More

II. Framework and Data

A. Network Analysis

A network is simply a collection of nodes—representing people, companies or countries, for example—and a set of links or “edges” connecting these individual nodes because of some relationship they have to each other. This very general and abstract characterization of a network can describe an enormous set of social, economic, political, and other kinds of arrangements. The co-authorship network is a collection of nodes representing the authors of law journal articles. The edges are the articles that are co-authored by any two or more legal scholars. Whereas citation and acknowledgment edges have a natural direction, running from the cited to the citing article, the co-authorship relationship does not have a natural direction from one author to the another. The graphs depicting this network are therefore known as “undirected” graphs.19 19.Matthew O. Jackson, Social and Economic Networks 20 (2010).Show More

Network graphs can be complicated mathematical objects. Although some of the most interesting structural features of a network are visible from the graph, it’s also helpful to have quantitative metrics to summarize and describe a network’s important properties that may not be readily apparent on visual inspection, as well as facilitate comparison with other networks. To do this, it’s necessary to introduce a little terminology.

We say that two authors are connected if they are co-authors themselves or if a chain of co-authors connects them to each other. These co-authorship links serve as the channel for information and influence of various kinds, and we are often interested in how far two authors are from each other in the network, since that will influence how effectively information and influence passes between them. An important concept in network analysis is the geodesic between any two connected authors, which is the set of links that form the shortest path between them.20 20.Id. at 32.Show More The distance between these authors is simply the number of those links.21 21.Id.Show More

Sometimes a network is not entirely connected but is composed of several components.22 22.Id. at 26.Show More A set of nodes constitutes a component if each node is connected to each other node. To illustrate, suppose that law professors co-authored only with scholars of the same gender and suppose that the network consisted of men, women, and non-binary scholars. The entire network includes all scholars, but it has three components. And clearly it would be important in describing such a hypothetical network to observe that it has three components, because it means that no scholar is connected to any other scholar of a different gender, and members of each gender are on an island, limited to the information possessed by others of the same gender.

In such a network, some components are likely to be larger than others, with the largest component probably being that of men, followed by the component made up of women and then the component made up of non-binary scholars. There are two common measures of the size of a component. The diameter of a component is the longest distance among all geodesics in the component.23 23.Id. at 32.Show More Finding the diameter involves finding all the shortest paths between nodes, and then identifying the longest of these paths. The component with the longest diameter is known as the giant component.

Note that components with more nodes do not necessarily have a longer diameter. To take an extreme example, suppose that the component of men scholars included Cass Sunstein and 500 other men, and Professor Sunstein co-authored an article with each of the 500 but that none of the 500 co-authored with each other. The graph of this component would look like a star, with Professor Sunstein in the middle. The shortest path between Sunstein and each other scholar would be 1, and the shortest path between any two of the 500 would be two (going through Sunstein). The diameter of this component would be two. Suppose that the component of women scholars had the same star structure, but with Jill Fisch at the center and 100 other women scholars. This component would have the same size as the men’s component, because the diameter would still be two.

Another important measure of the size of the component is average path length.24 24.Id. at 33.Show More This is simply the average of all geodesics—shortest paths—between nodes in the network. This measure captures the fewest authors connecting a typical pair of authors in the network, and the measure corresponds to the intuitive notion of the “degrees of separation” between two people in a network.

In addition to wanting to describe the size of a network, its various components, and how close its nodes are to each other, it’s often important to describe the properties of individual nodes. For example, we may want to know if there are particular legal scholars who are especially well connected—who frequently co-author—and whether they resemble their co-authors in certain ways. One way of measuring the connectedness of a professor in the co-authorship network is simply to count the number of her co-authors. The number of her co-authors is known as the professor’s degree.25 25.Id. at 29.Show More Using this measure, we can get a sense of how connected the typical law professor is by looking at the average degree among all professors in the network.

Given our interest in the role of co-authorship in allocating professional opportunities and facilitating intellectual cross-pollination, we are interested in measuring how the characteristics of individual authors are correlated—positively or negatively—with the characteristics of her co-authors. For example, do professors tend to seek similarity in co-authorship, writing with other scholars of the same gender, race, or generational cohort? Or do they tend to seek complementarity, writing with scholars whose differences might result in a more efficient allocation of labor or a more creative output? To measure the tendency for scholars to co-author with other scholars with similar attributes—a network property known as homophily—I use a measure of correlation known as the assortativity coefficient and calculate it for scholars’ gender, minority status, and degree.26 26.Mark E.J. Newman, Mixing Patterns in Networks, 67 Physical Rev. 2 (2003).Show More The coefficient is positive if scholars tend to co-author with scholars who share the same traits, and it is negative if they tend to co-author with scholars having different traits.

An important characteristic of social networks is the amount of clustering or cliquishness. We may want to know, for example, whether it’s typical for a scholar’s co-authors to co-author with each other or whether certain professors are central in some sense to the scholarly network. A professor with many co-authors may be well connected, but a professor at the center of a dense, interconnected part of the co-authorship network may be important because she facilitates other collaborations and network connectivity. There are two measures of the amount of network clustering around individual authors. The transitivity—also known as the triadic closure or overall clustering—of the network is calculated by determining, for each individual author, how frequently any two of her co-authors are themselves co-authors.27 27.Jackson, supra note 18, at 35.Show More The second measure is the average clustering coefficient.28 28.Id.Show More The measure is calculated for each scholar, taking the number of co-authorship relationships among her co-authors as a fraction of all possible such relationships, and averaging across all authors. Because the average clustering coefficient weights the clustering coefficients of all authors equally (i.e., regardless of how many co-authors an author has) it will give greater weight to authors with fewer co-authors than the transitivity measure of clustering.

B. Data

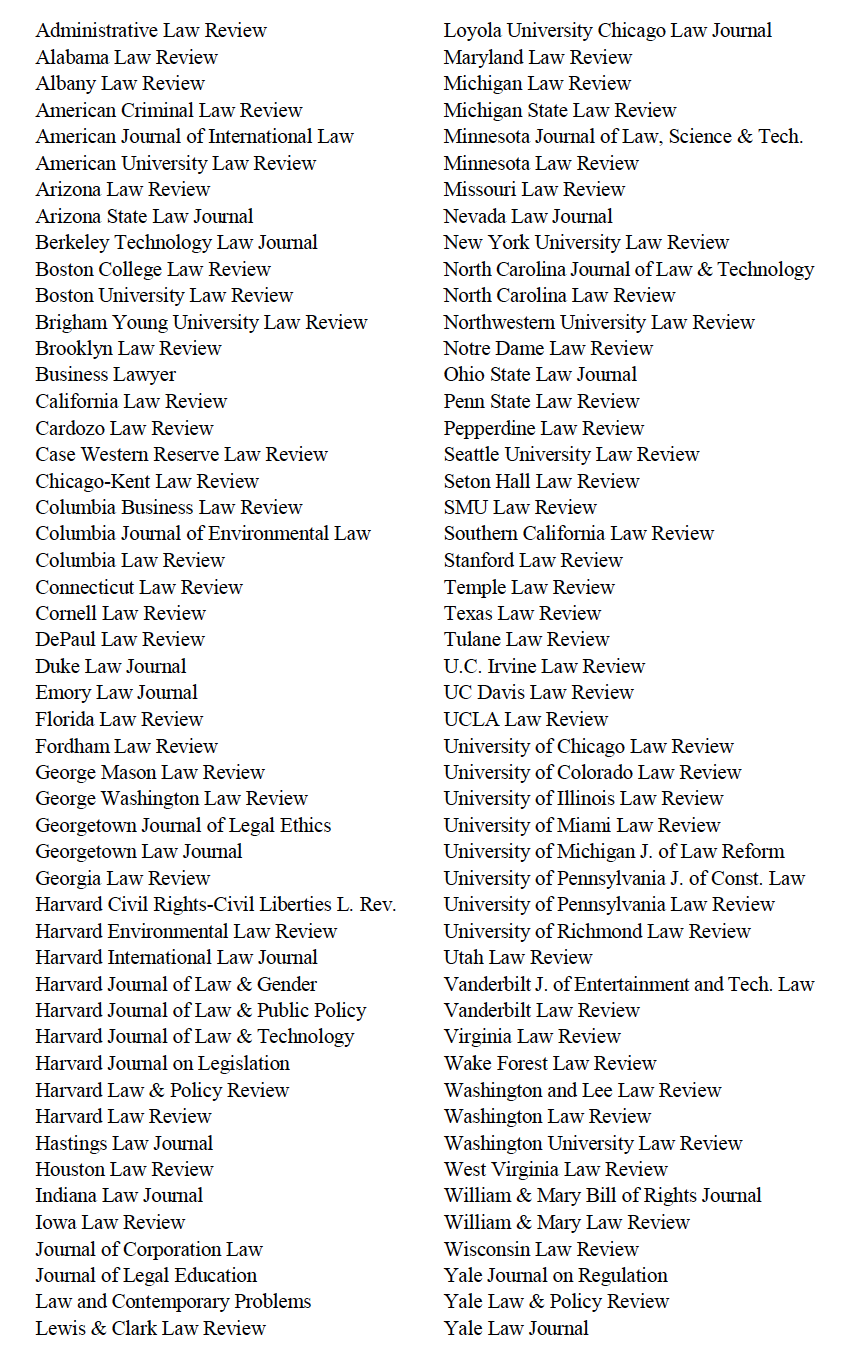

The raw data used to create the network is all articles published in the top 100 general and specialty law reviews as ranked by Washington and Lee for the period 1980–2019. By limiting my sample to student-edited law journals, I will likely underestimate the amount of co-authorship by legal scholars overall, since much co-authored work with an empirical component appears in peer-reviewed journals such as those at the intersection of law and economics or law and psychology. Including these journals, however, would likely only amplify the increase in co-authorship I observe over time, since the emergence of empirical legal studies is a relatively recent phenomenon. The journals included in the sample are listed in Table 1 in the Appendix. I then removed student notes and comments, articles with more than 10 authors, and articles that did not have at least one author who was a professor. This left a total of 67,472 articles. I then identified the 9,320 authors who published more than one article during the period 1980–2019, who I call “scholars.” Focusing on scholars eliminates articles by practitioners, students, and judges that were not filtered at an earlier stage, allowing me to limit my analysis to the social network of research-active authors.

Data on authors’ gender, minority status, institutional affiliation, and age were collected from the American Association of Law Schools (AALS) Directory of Law Teachers. These data are collected from surveys and are self-reported. The Directory includes lists of minority teachers beginning in 1986 and lists LGB professors beginning in 1996.29 29.For racial minorities, I used lists published in the 1986, 1989, 1990, 1991, 1992, 1996, 2000, 2004, 2007, 2011, 2014, and 2019 editions. For sexual minorities, I used lists from the same years, beginning in 1996.Show More I identify a scholar as a minority or member of the LGB community if they ever appear on these lists. There may be reasons why scholars in different time periods or at different institutions may be less likely to submit this information to AALS, which may lead to underreporting of the number of such scholars. I code any scholar whose name does not appear on the lists of minority or LGB professors as not belonging to those communities. The Directory reported gender information from 1986–2011 and I use these data when they are available. For any author whose gender is not reported in the Directory, I first matched the author’s given name with the 200 most popular baby names by gender as reported by the Social Security Administration for each decade from the 1940s to the 2010s. Finally, a student research assistant supplemented the data by doing internet searches of the remaining scholars’ names and assessing their genders. The gender of any scholar for whom I could not obtain data using the procedure above is coded as missing.

III. The Emergent Small World of Legal Academia

In this Part, I analyze the scholar co-authorship network for each of the last four decades. I describe the growth and evolution of that network alongside the overall rise in co-authorship within legal scholarship and report how the distribution of co-authorship is “fat tailed,” with more scholars doing solo-authored work and more scholars having many co-authors than one would expect if co-authorship relationships were formed randomly. Finally, I evaluate whether the network of legal scholars can be described as a “small world” as that term is used in the network analysis literature, such that even a community of very many law professors is densely connected with relatively few degrees of separation between its members. I find that the law professoriate is, in fact, a small world and that it is getting smaller. Even as the number of legal scholars has grown significantly, they are more closely connected to each other than ever before.

A. Network Growth

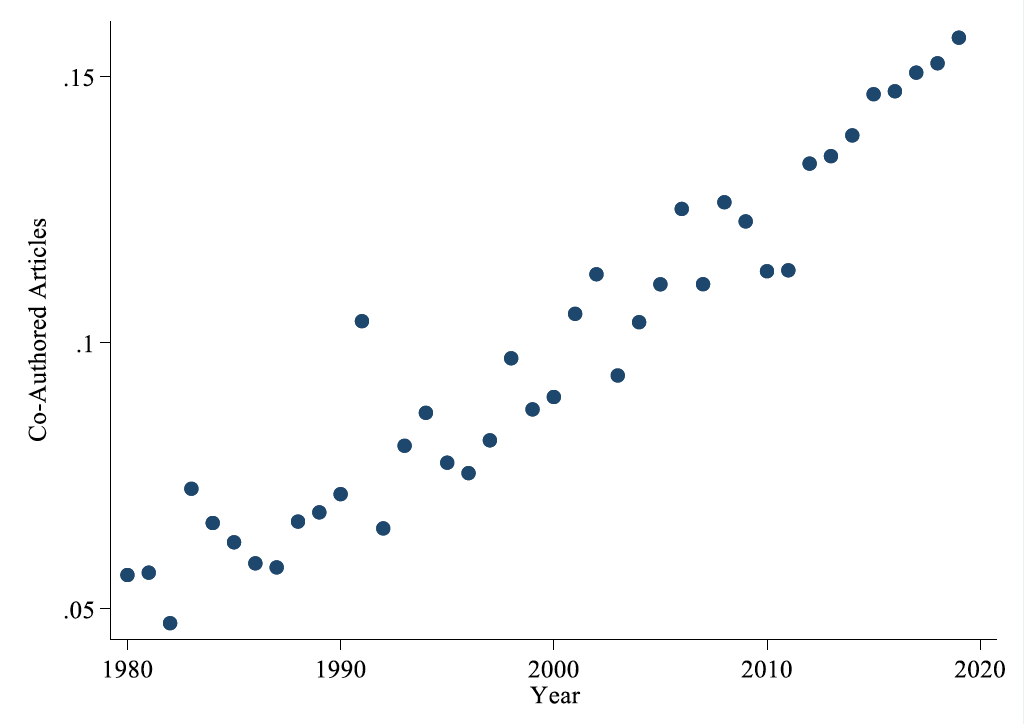

There are more legal scholars and more legal scholarship being published than ever before. In the 1980s—the first decade of my sample period—there were 3,409 scholars publishing and there were 9,742 articles published. In the 2010s, by contrast, there were 5,595 scholars and 18,159 published articles. And although the number of both solo-authored works and co-authored articles has increased over time, there has been a much more dramatic increase in co-authored work. The absolute number of articles with only one author increased from 9,139 in the 1980s to 15,648 in the 2010s, but the number of articles with at least two legal scholars quadrupled from 603 in the 1980s to 2,511 in the 2010s. Figure 1 shows the share of all published articles that were co-authored each year by scholars. Not only do the data show that this share has tripled from roughly 5% in the early 1980s to over 15% by 2019, but the trend is striking for its steady increase over the entire time frame. The increase in co-authorship over the last forty years is clearly not just a blip, but it reflects a persistent and growing shift in how legal scholarship is produced.

The long time period of my sample provides some context for earlier studies on legal co-authorship and raises questions about the underlying dynamics generating the trend. In earlier work, Professors Ginsburg and Miles reported an increase in the share of co-authored articles published in the top 15 law reviews from 2000 and 2010, and in two peer-reviewed law journals from 1989 to 2011.30 30.Ginsburg & Miles, supra note 6, at 1785.Show More They attributed this increase to the rise of empirical legal studies.31 31.Id. at 1785 (“[R]esults support the view that specialization, and specifically the growth of empirical scholarship, has contributed to the trend of coauthorship in legal academia.”).Show More Legal scholarship that incorporates quantitative analysis is likely to be especially suitable for co-authorship, bringing together scholars with expertise in quantitative analysis with topic matter specialists.

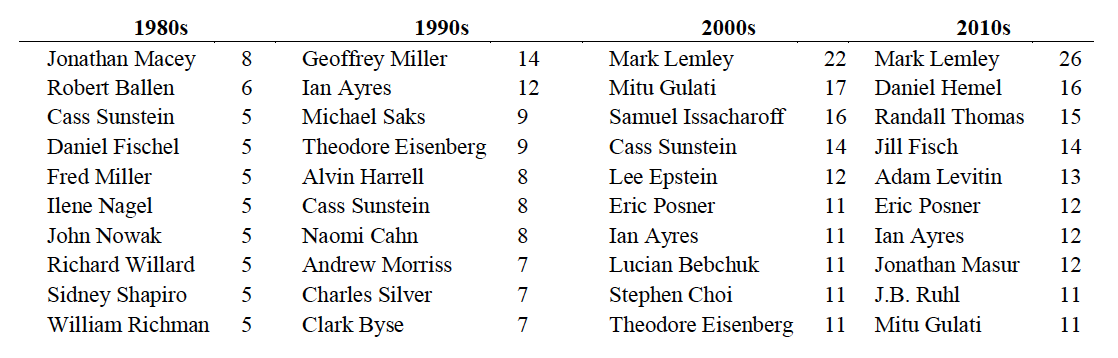

On the one hand, an examination of the scholars who co-author most lends support to this view. Table 2, in the Appendix, lists the legal scholars in each decade with the most co-authors. These lists include several scholars—such as Ian Ayres, Mitu Gulati, and Ted Eisenberg—who do a great deal of empirical scholarship. On the other hand, the lists also include many scholars who do not do empirical work, and it is also notable that the trend in increasing co-authorship had already begun by 1980 and continues unabated through the present. It is difficult to place a specific start date for the contemporary rise of empirical work, but some sociologists place it in the mid-1990s,32 32.Mark C. Suchman & Elizabeth Mertz, Toward a New Legal Empiricism: Empirical Legal Studies and New Legal Realism, 6 Ann. Rev. L. & Soc. Sci. 555, 556 (2010) (“Since the mid-1990s, several groups of scholars have championed a renewed dialog between law and social science.”).Show More and the Journal of Empirical Legal Studies did not begin to be published until 2004.33 33.Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, Wiley Online Libr., https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/loi/17401461 [https://perma.cc/6GXQ-LCEK] (last visited Oct. 28, 2022).Show More Moreover, the trend toward co-authorship is evident looking at the top 100 law journals and excluding the peer-reviewed journals where much quantitative legal scholarship is published, such as the Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, the Journal of Law & Economics, and the American Law and Economics Review. Including peer-reviewed journals would likely amplify this trend.34 34.See Ginsburg and Miles, supra note 6, at 1785 (“Coauthored articles were far more common in . . . [the Journal of Legal Studies and Journal of Law, Economics and Organization] . . . than in the general interest, student-edited law reviews.”).Show More

Figure 1: Co-Authored Share of Articles

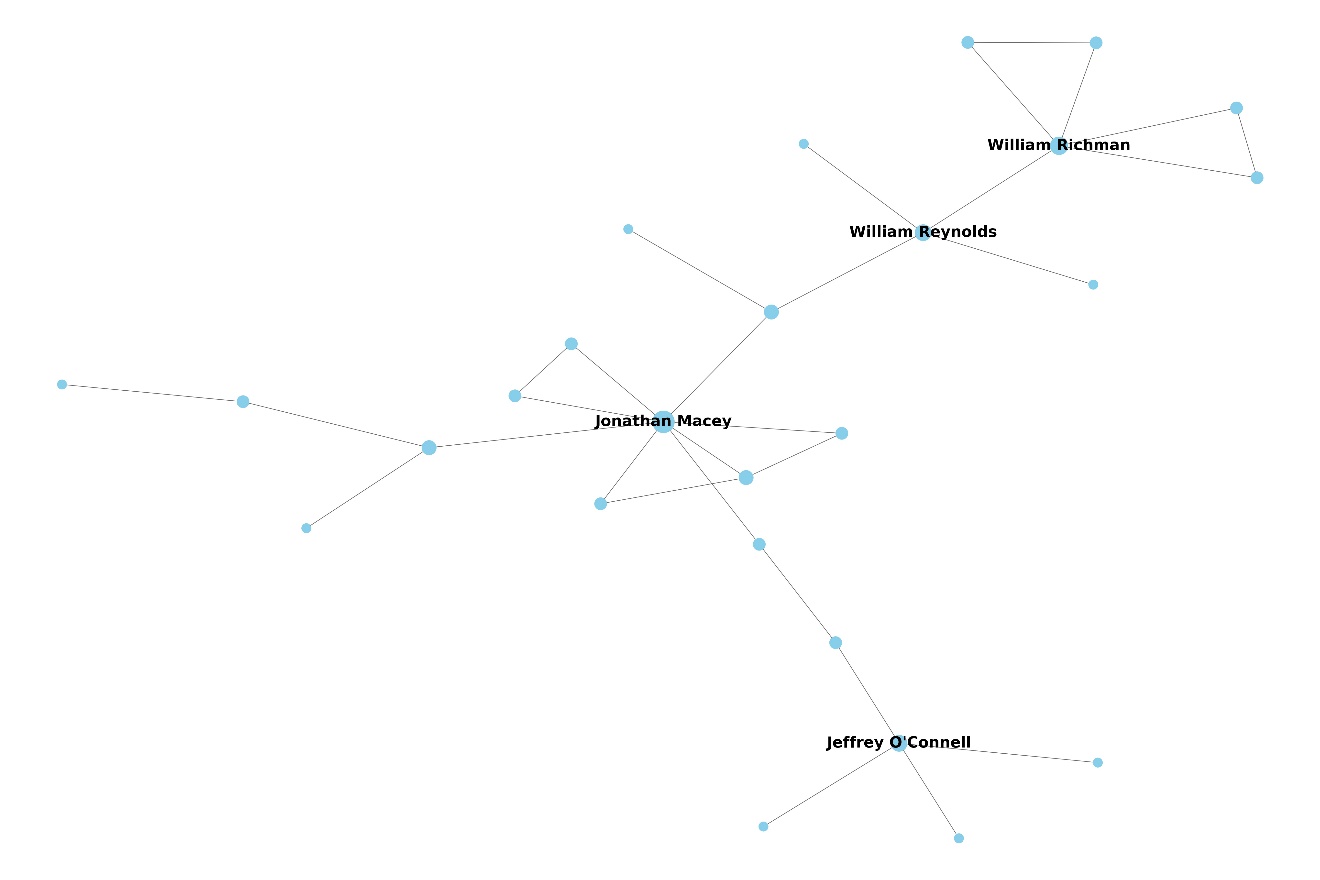

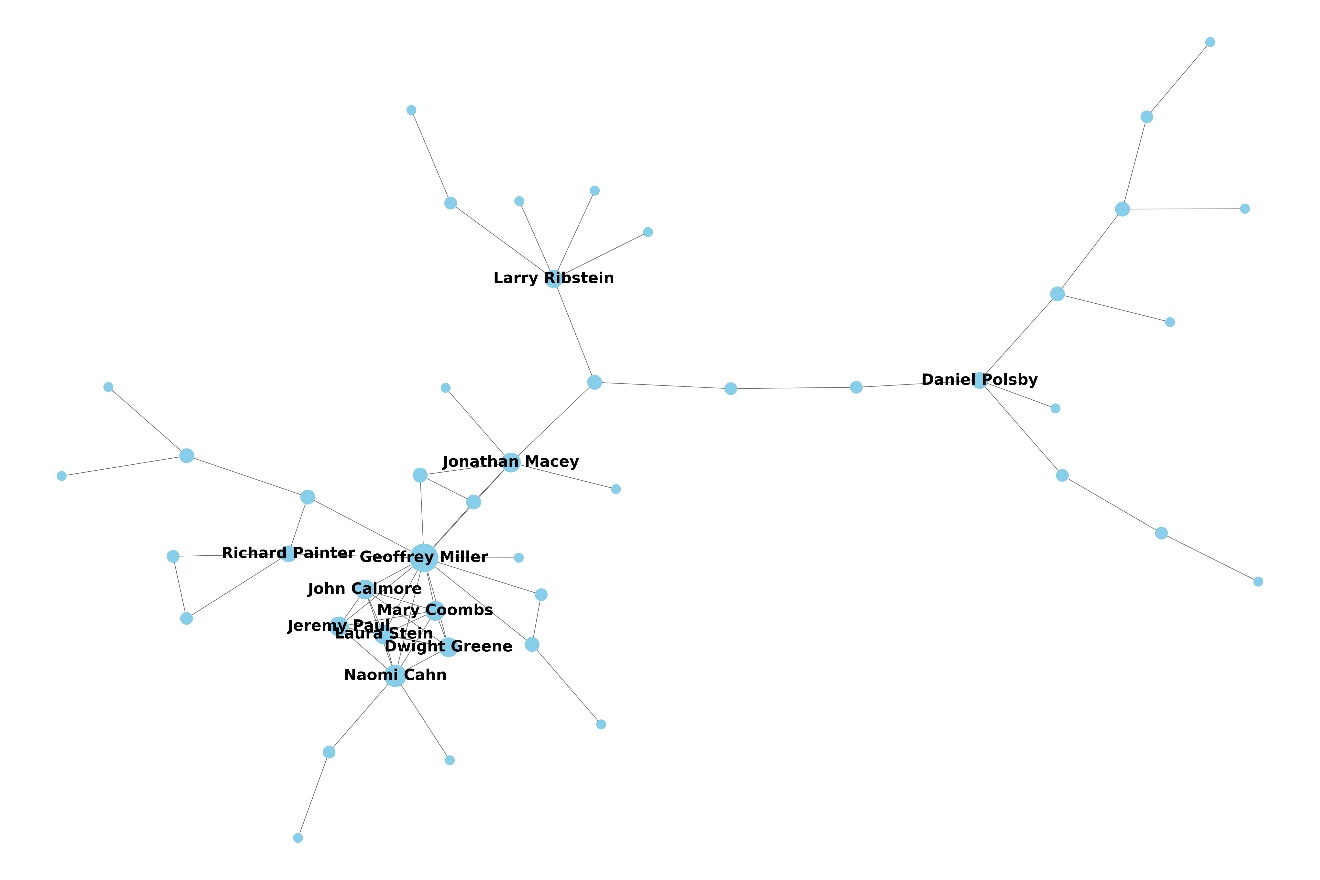

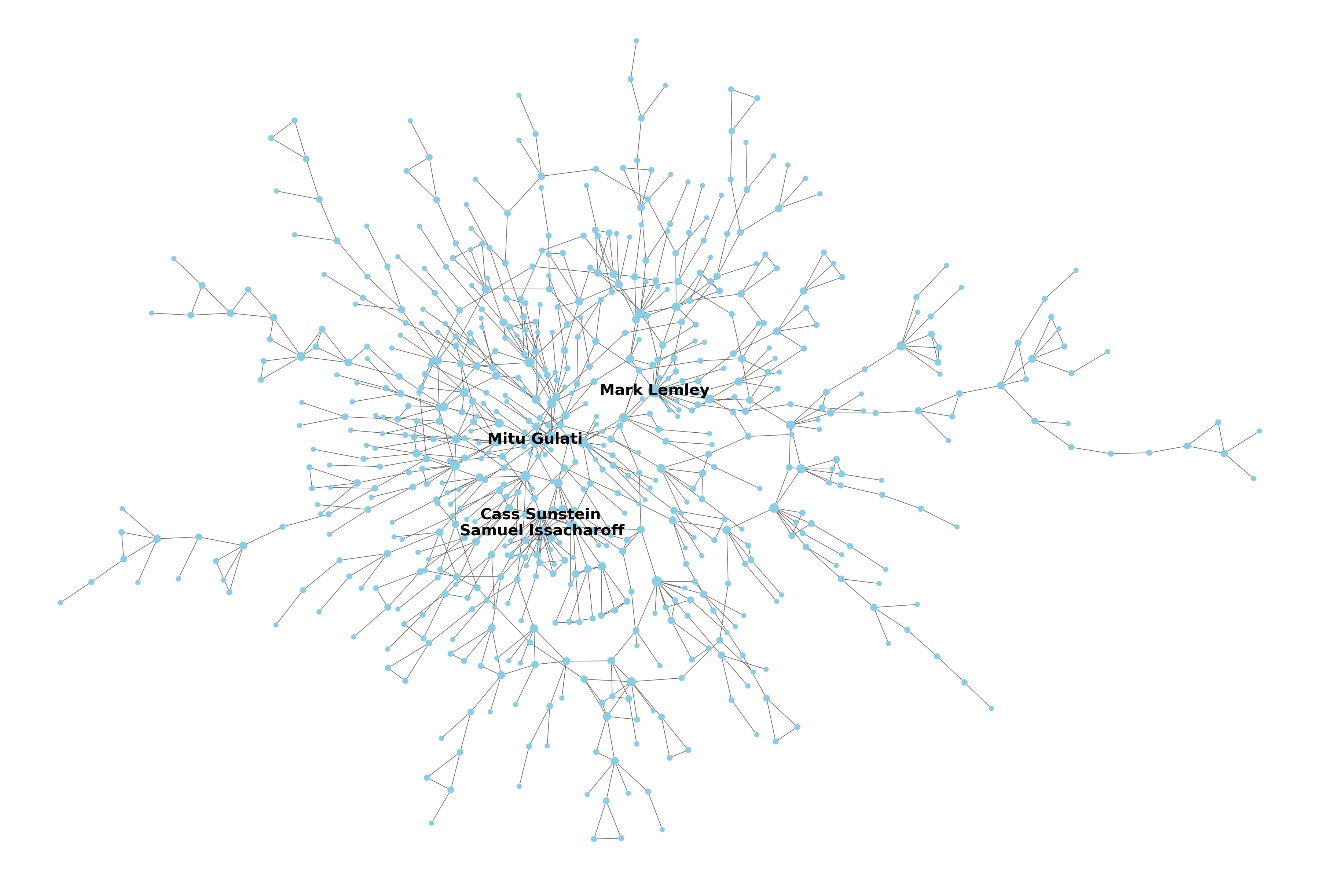

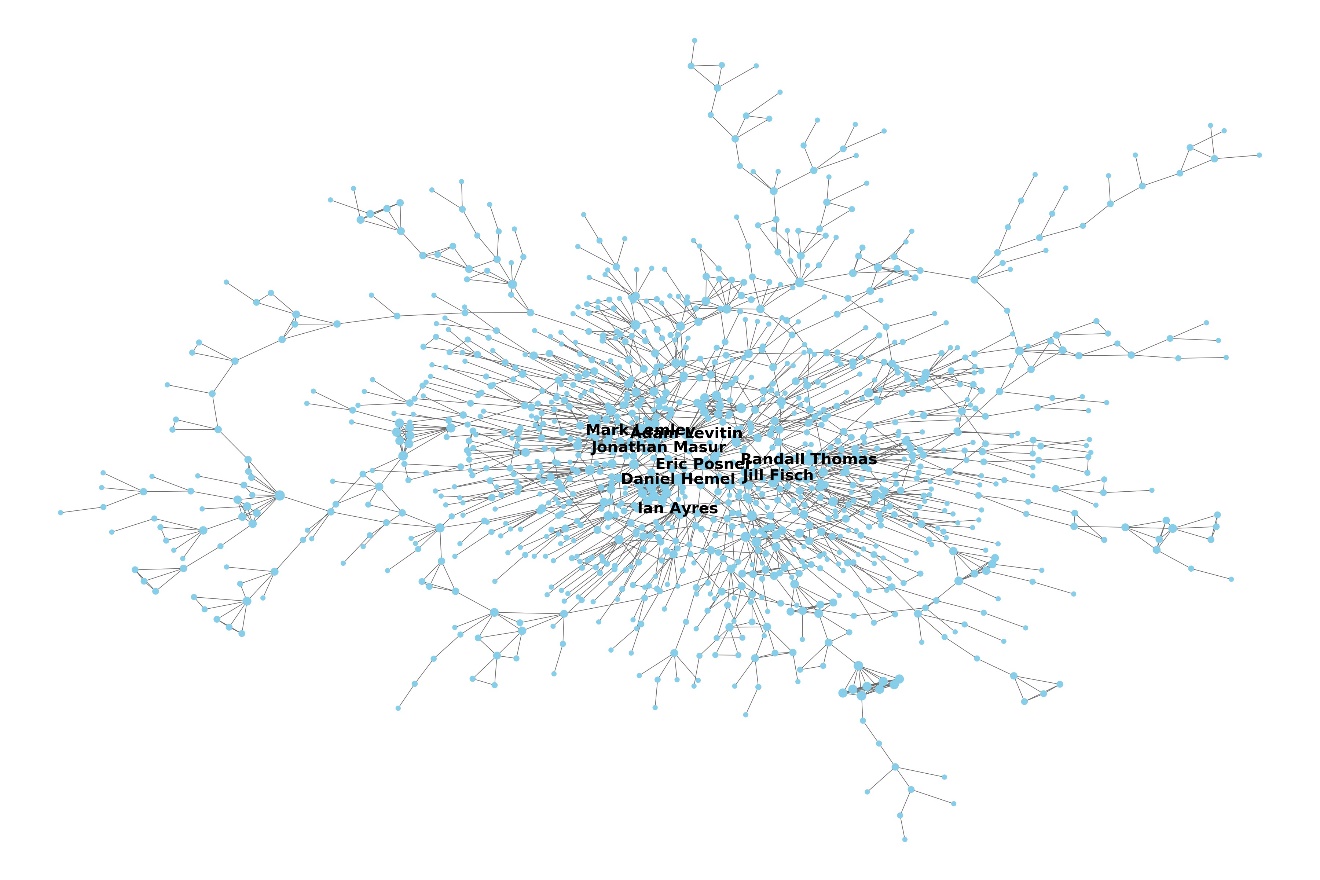

Over the last forty years then, there has been an increase in both the number of legal scholars—the nodes—and the number of co-authorship relationships—the edges. Figures 2–5 show the staggering increase in the size of the largest component of the co-authorship networks for each of the past four decades. In 1980, this component included only 26 scholars, making up 3.4% of the entire professor network. Things look dramatically different in 2010s, where the largest component of the scholarly network included 1,226 scholars and made up 50.9% of the entire network. Thus, a much greater share of the professoriate is now connected to each other through co-authorship linkages. The hubs of each giant component are those with the most co-authors, and they are indicated on each graph by their names. As co-authorship has become more prevalent, the threshold for being one of these hubs has increased as well. In the 1980s and the 1990s, the hubs were scholars with at least four co-authors. In the 2000s and the 2010s, these were scholars such as Ian Ayres and Cass Sunstein with at least twelve co-authors. The ten scholars with the most co-authors by decade are listed in Table 2, in the Appendix. Whereas the most connected professor in the 1980s was corporate and securities law scholar Jonathan Macey with eight co-authors, in the 2000s and 2010s the most connected scholar was IP scholar Mark Lemley with 22 and 26 scholar co-authors in those decades, respectively.

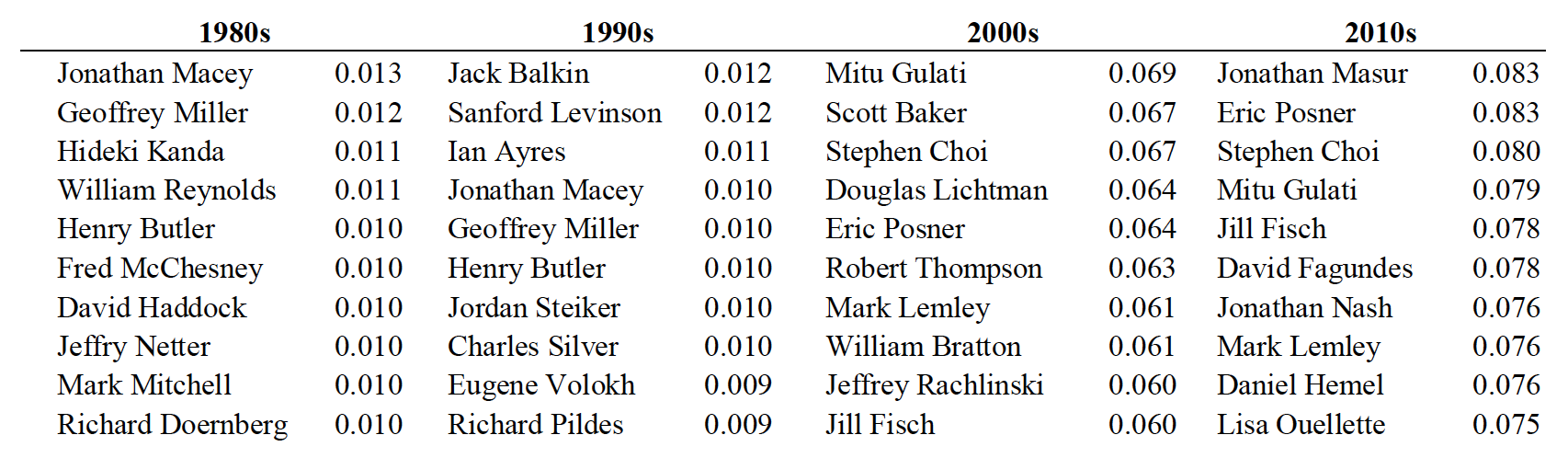

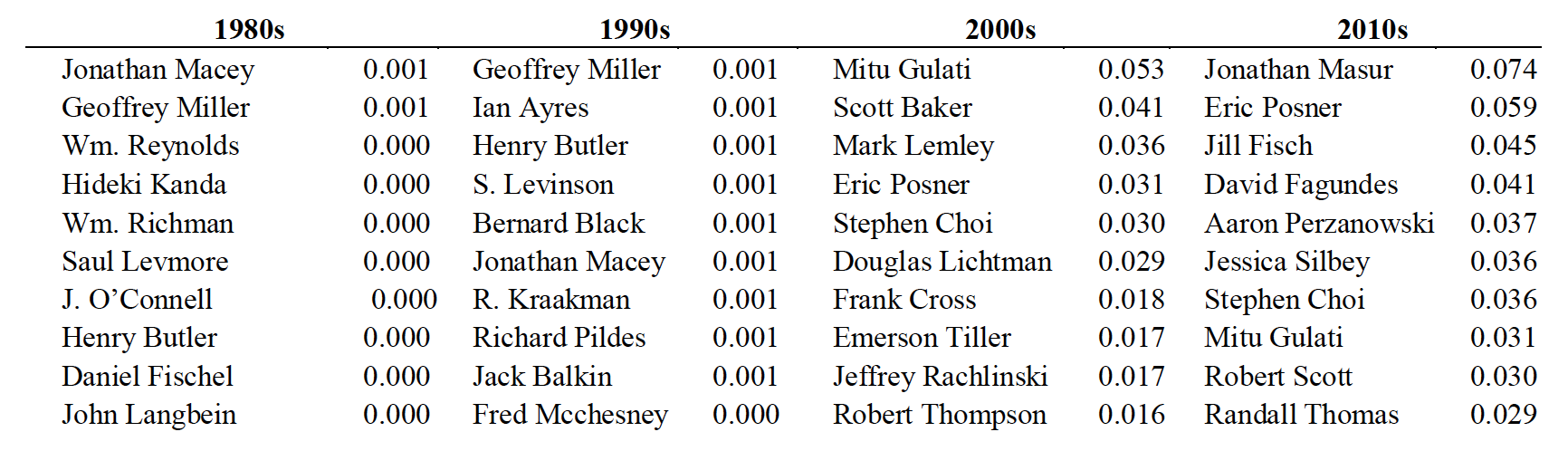

The number of a scholar’s co-authors—their degree—is only one measure of their significance to the co-authorship network, and there are other measures that reflect other concepts of a scholar’s centrality. For example, closeness centrality measures the average distance between a scholar and the other scholars in the network through co-authorship relationships. This measure is conceptually analogous to typical “degrees of separation” between one scholar and all the other scholars. An alternative measure of a scholar’s centrality or importance to the network is her betweenness centrality. This measure captures how often the shortest path between any two other professors runs through the scholar.35 35.For details about the calculation of these centrality measures, see Jackson, supra note 19, at 39.Show More

Lists of the top ten scholars by these two measures of centrality are in Tables 3–4 in the Appendix. There is a fair amount of overlap between the scholars identified as the most closely connected using the closeness centrality measure and the scholars through whom other scholars are linked using the betweenness centrality measure. These lists include prolific scholars who frequently co-author—especially in the areas of corporate and securities law—such as Jill Fisch, Mitu Gulati, and Steven Choi, but also a miscellaneous group of other scholars writing in areas such as IP, behavioral economics, and administrative law.

|

Figure 2: Legal Scholar Co-authorship Network 1980-1989

|

|

Figure 3: Legal Scholar Co-authorship Network 1990-1999

|

|

Figure 4: Legal Scholar Co-authorship Network 2000-2009

|

|

Figure 5: Legal Scholar Co-authorship Network 2010-2019

|

B. Characteristics of the Network

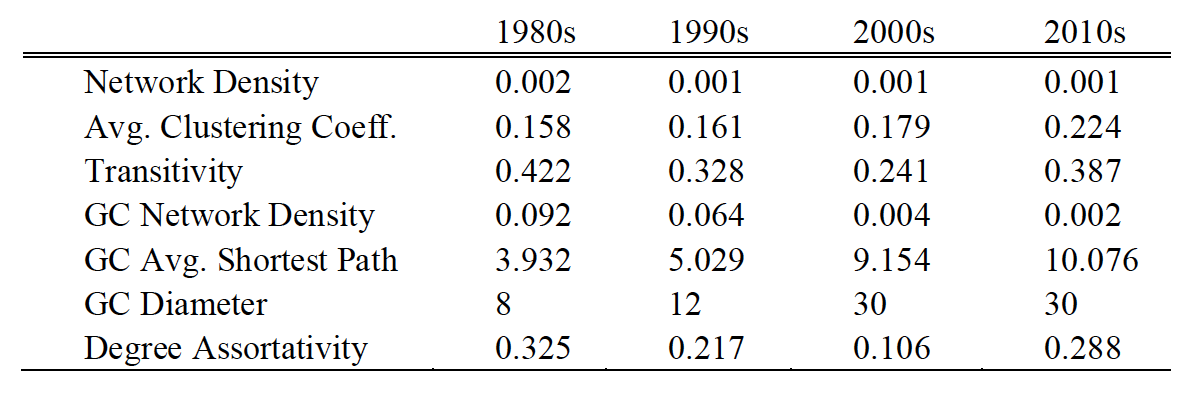

The scholarly network contains many more scholars and is much more connected than it used to be. In this Section, I conduct a closer investigation of the law co-authorship networks that emerged in each of the last four decades, comparing them using the various summary statistics described in Part I to understand how the scholarly network has evolved over time. These summary statistics are reported in Table 1. I constructed a separate co-authorship network for each decade and reported the density, average clustering coefficient, and transitivity of those networks. For the giant component of each network, I also reported the density, the average shortest path (geodesic) between scholars, and the diameter.

Table 1: Co-authorship Network Statistics by Decade

One measure of a network’s connectedness is its density. The network density is simply the share of all possible links between co-authors that are present. As the size of the scholar network has increased over the last forty years—from 760 to 2,410 scholars—its density has declined; there were fewer co-authorship relationships as a share of possible relationships in each successive decade than the one before. This is an almost inevitable consequence of the growth of the network, because adding the th scholar to the network means adding possible links, and so as grows, the set of possible links grows at an increasing rate.

Recall that there are two measures of cliquishness or clustering in the network—transitivity and the average clustering coefficient. Interestingly, these two measures exhibit different patterns over time. The average clustering coefficient has increased over time, indicating that a typical scholar’s co-authors are more likely to co-author now than they were before. Transitivity—or overall clustering—however, declined in the 1990s and then the 2000s before increasing again in the 2010s. What explains these different patterns? Recall that the key difference between average clustering and overall clustering is that overall clustering gives greater weight to scholars with more co-authors. The different temporal patterns from 1980–2010 could be explained by a general increase in co-authorship during this time period among small cliques, while some of the “star” scholars with many co-authors during the early period continued to add co-authors in the 1990s and 2000s who were not themselves well connected. This pattern could arise, for example, if star scholars are more senior members of the academy who chose in the 1990s and 2000s to co-author with relatively junior scholars.

The last row of Table 1 reports the degree assortativity of the four networks. This captures the tendency for scholars with many co-authors to work with other scholars with many co-authors. This statistic follows the same pattern over time as network transitivity. Scholars who were well connected were less likely to co-author with scholars who were also well connected from 1990–2010 than in the 1980s. This statistic is consistent with the idea that “star” scholars in the 1990s and 2000s were more likely to co-author with scholars who were not themselves well connected.

Although the giant component of the scholarly network has grown enormously in terms of its coverage of the entire network—covering 50.8% of the 2010 network and having a diameter of 30—many scholars remain only loosely connected. The density of the giant component has followed the same trend as the entire network and is smaller than it was in the 1980s. Even more importantly for understanding how close scholars are to each other through chains of co-authorship, the average shortest path increased from 3.9 in the 1980s to 10.1 in the 2010s, meaning that, for any two randomly chosen scholars, the expected “degrees of separation” is nine intermediate co-authors.

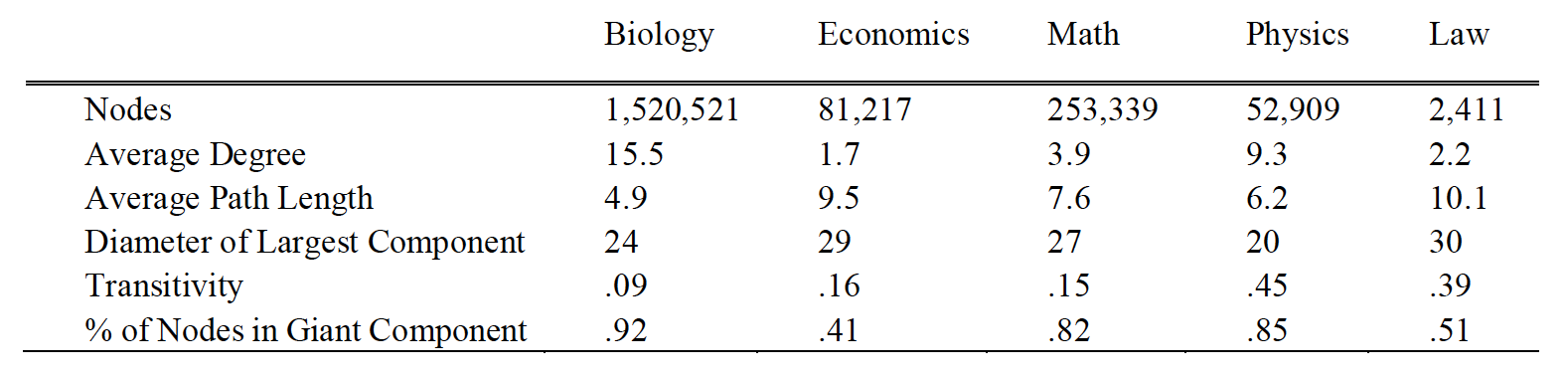

Since it is hard to know what to make of these statistics in isolation, I have focused on how they have evolved over time to understand the trajectory of legal academia. Another way of contextualizing these numbers is by comparing the network of legal scholars with the co-authorship networks in other academic disciplines. Table 2 reports statistics on the co-authorship networks in Biology, Economics, Math and Physics and compares them with statistics for the 2010s co-authorship network of legal scholars.36 36.The data come from Jackson, supra note 19.Show More

Table 2: Comparison of Co-authorship Networks

Even as the number of published legal scholars has grown over time, there are only a small fraction as many law professors publishing in U.S. law journals as there are scientists, economists and mathematicians publishing in their fields. The second row reports the average degree—the average number of co-authors—among scholars in each field. Researchers in the natural sciences typically have many more co-authors than scholars in other fields, due to the collaborative nature of work that is often funded by outside grants, cooperation between theorists and experimental researchers, and norms for giving co-authorship credit within research labs. The model of knowledge production in law is much closer to that in economics, and so comparisons between law and economics will be especially useful.

It is noteworthy that, notwithstanding the historical scarcity of co-authorship in law37 37.Meyerson, supra note 5, at 548.Show More and the trend toward increasing co-authorship in economics,38 38.Andy H. Barnett, Richard W. Ault & David L. Kaserman, The Rising Incidence of Co-Authorship in Economics: Further Evidence, Rev. of Econ. & Stat. 539 (1988).Show More the average number of co-authors among legal scholars has overtaken that among economists. Focusing on the giant component of each scholarly network, the giant component in law has a longer diameter than in any of these other fields but makes up a much smaller share of the network of scholars than the giant components in biology, physics, and math. Virtually all biologists, physicists, and mathematicians are connected to each other through a single co-authorship network. By contrast, the giant component includes only 41% of economists and 59% of legal scholars. But these numbers do show that that there has been greater consolidation of the legal scholar network than among economists.

The average path length—of 10.1—between legal scholars is longer than in the other networks, indicating that legal scholars are typically more degrees removed from each other than scholars in other fields. The biology and physics networks are particularly dense. But the difference between the average path length in economics and in law is modest, only a difference of half a degree, on average. This suggests that economists and law professors are situated similarly close to each other, as measured by co-authorship relationships. Interestingly, transitivity in the legal scholar network is considerably greater than in all other fields except physics. This means that a legal scholar’s co-authors are more likely to co-author with each other than the co-authors of scholars in the other fields, suggesting a higher degree of cliquishness in law.

C. Co-author Distributions

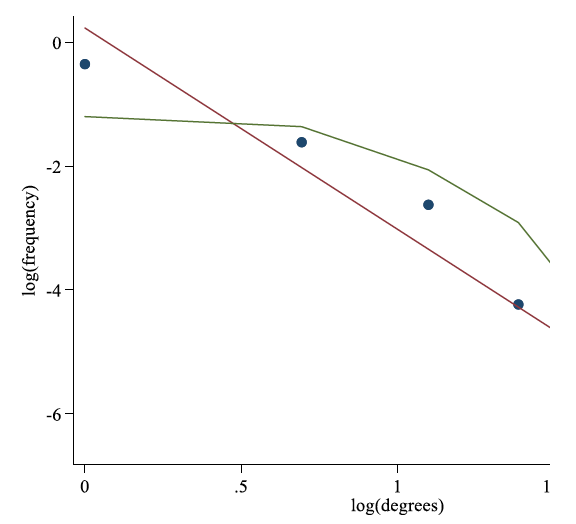

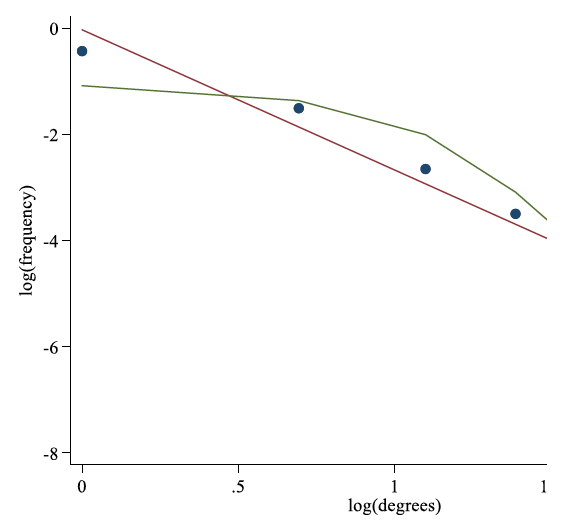

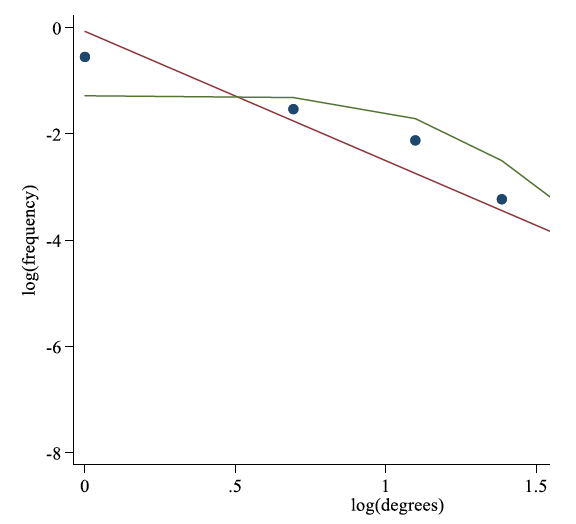

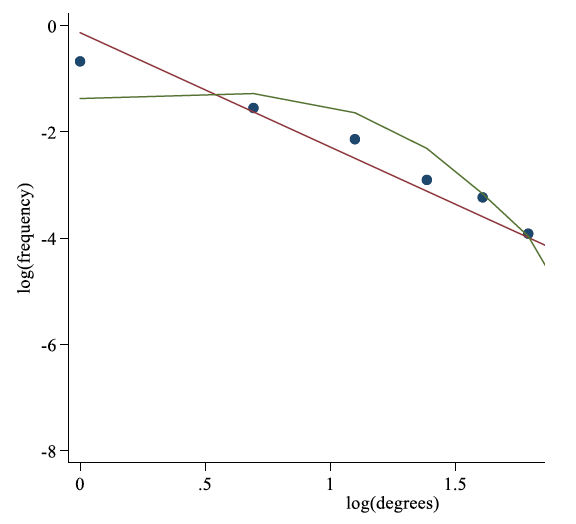

In the 1980s, the average number of scholar co-authors was only 1.44, and by the 2010s, the average number of scholar co-authors had increased to 2.2. But focusing solely on the average number of co-authors ignores considerable nuance in how co-authorship has evolved. For example, we should want to know whether this increase in the average number of co-authors is being driven by an increase in co-authorship across the board—whether all legal scholars are co-authoring more—or whether the increase has been driven by a relatively small number of scholars. We can see this by looking beyond the average number of co-authors to examine the entire distribution of co-authors among scholars. Let be the share of scholars in the network that have co-authors ( stands for “degrees”). Examining the distribution of scholars by number of co-authors, and how that distribution has changed over time, can shed light on how co-authorship relationships form and why the average has increased over time. But rather than plot graphs showing the share of scholars on the vertical axis against the number of co-authors on the horizontal axis, I transformed these numbers by taking the natural logarithm of each, for ease of visualization and for reasons discussed below. As a result, Figures 6–9 show graphs plotting the natural log of against the natural log of for each decade of the sample period.

Figure 6: Co-author Distribution 1980s |

Figure 7: Co-author Distribution 1990s |

Figure 8: Co-author Distribution 2000s |

Figure 9: Co-author Distribution 2010s |

The dots in each graph represent the actual distributions showing the share of scholars with a specified number of co-authors—after taking the natural log of each number. For example, in Figure 8, consider the third blue dot from the left. This dot corresponds to the roughly 13.5% of scholars in the 2000s network (the natural log of which is about -2) who had 3 co-authors (the natural log of which is about 1.1). To better visualize the distribution, the red line shows the straight line that best fits the dot pattern.

What process of co-authorship formation could have led to these distributional patterns? One useful benchmark is a process whereby co-authorship relationships are formed randomly, as though each scholar when deciding who to write with picked a name out of the hat of all legal scholars. A network generated in this way would have a graph in which the distribution of degrees was much more curved than the distributions we observe among legal scholars. Particularly in the 2000s and 2010s, the distribution of co-authorship is reasonably well-represented by the straight red line.

To see the difference, the curved lines in green show the degree distributions that would result from random graphs. For each decadal network, I used the number of scholars and the number of links from the actual network but assigned those links randomly. The relative linearity of the distribution as compared with the random network means that the actual co-authorship distribution has more scholars with very many co-authors and more scholars with very few co-authors than would be expected if co-authorship relationships were formed at random. This is known as a “fat-tailed distribution.”

What kind of process would lead to these fat-tailed distributions? One possible mechanism for the formation of the law-scholar network is known as preferential attachment. The idea of this process is that when someone is choosing who to write with, they are more likely to pair up with someone the more co-authors that person already has. There are a variety of reasons why preferential attachment could arise in the network of legal scholars. For example, it could be that scholars at some law schools are more likely to be co-authors than at others, and that people tend to write with their colleagues. It could be that some scholars work in areas where co-authorship is more common, so that scholars working in empirical legal studies tend to have many co-authors whereas scholars in other areas tend to write solo-authored works. Or it could be that co-authorship is associated with an increased scholarly profile or a personal preference for writing with others, such that people with many co-authors tend to seek more co-authorship projects, or other scholars seek them out.

D. A Small World

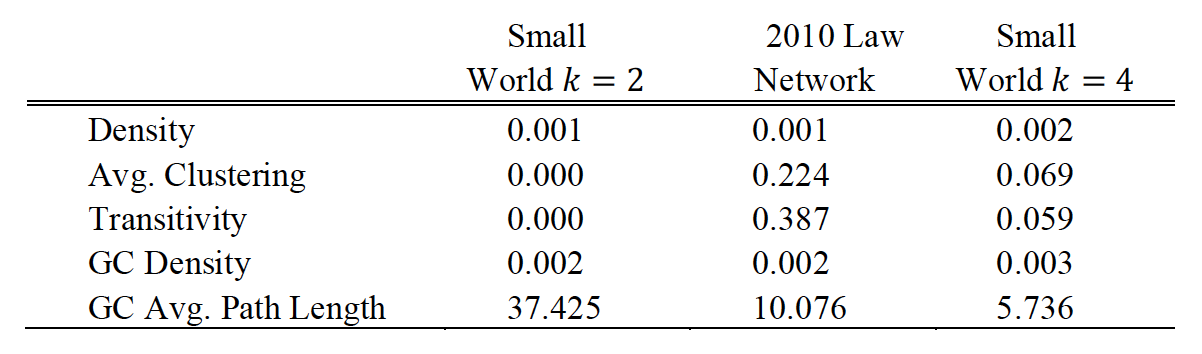

As the number of legal scholars has grown, technological innovations such as email, videoconferencing, online platforms, and cheaper travel have made it easier for scholars to identify potential collaborators and work with scholars at other institutions or in other time zones. For whatever reason, the rise of co-authorship has brought the network of legal scholars closer together. But how close? One way of answering this question in the network literature is to ask whether legal scholars inhabit a “small world.” Following the scholarly literature, I say that the network of legal co-authorship has small-world properties if (1) the number of scholars is much larger than the average number of co-authors; (2) the giant component covers a large share of the entire network; (3) the average shortest path in the giant component is small;39 39.Specifically, the average shortest path should be of the same order as .Show More and (4) if there is significant clustering, so that the transitivity of the network is much larger than the average number of co-authors divided by the number of scholars.40 40.In this I follow Sanjeev Goyal, Marco J. van der Leij & José Luis Moraga‐González, Economics: An Emerging Small World, 114 J. Pol. Econ. 403 (2006). Goyal et al. builds on the seminal analysis of Duncan J. Watts & Steven H. Strogatz, Collective dynamics of ‘small-world’ networks, 393 Nature 440 (1998).Show More To evaluate the network of legal scholars along these dimensions, I benchmark its small-world features against the network of economics co-authorship and also against randomly generated small-world networks.

Consider the first property. In the last four decades, the average number of a legal scholar’s co-authors has increased from 1.4 to 2.2 while the number of legal scholars has increased from 760 to 2,410. Not only is the number of legal scholars much larger than the average number of co-authors, but the ratio of the two is increasing over time. Thus, the legal scholar network satisfies the first requirement for a small world, and even more so in recent years. And the second small-world property is satisfied too. The giant component, which covered only a very small part of the scholar network in the 1980s, now covers roughly 51% of the network. By comparison, the giant component of the economics co-authorship network covers 40% of the network, which scholars concluded is still large enough to be indicative of a small world.41 41.Goyal et al., supra note 39, at 408.Show More

The third small-world criterion is that the average shortest path in the giant component is “small.” Although the average shortest path of the giant component has increased modestly over time, it remains relatively small. Specifically, it is conventional to define the average shortest path as small when it is of the same order of magnitude as the natural log of the number of nodes in the network.42 42.Id. at 405.Show More In the 2010s, the average shortest path of the giant component was 10.1 and the log of the number of scholars was 7.8. These are of the same order of magnitude because if we multiply 7.8 by 10 we get a number that is much larger than 10.1. Another way of thinking about the smallness of the average path length is by comparing it to the average shortest path in the economics network. As noted above, the average shortest path in economics is 9.5, so the two have similar average path lengths and the third requirement for the law network to be a small world is satisfied.

Finally, how strong is the clustering in the law network? From Table 1, we see that the transitivity of the law network declined from 0.42 to 0.33 to 0.24 and increased back to 0.39 in the 2010s. Is this a lot of clustering? One way to answer this question is to compare the overall clustering with the clustering that would be expected if the network were randomly generated. In that case, the transitivity of the random network would be approximately the average degree of a scholar divided by the number of scholars. In the last four decades, the randomly generated transitivity would be 0.0019, 0.0012, 0.0010 and 0.0009—far less than the amount of clustering than we observe. The actual amount of overall clustering in the network over the last four decades is 214, 269, 235, and 352 times the amount of clustering predicted in a random network. We can also compare transitivity against the network of economists. The clustering in the law network is not as high as the clustering in the economics network—where the clustering coefficient was 700 times what one would expect in a random network—but the two are not far apart, so we still conclude that the fourth small-world requirement is satisfied. Since all four conditions are met, we conclude that the network of legal scholars is a small world, and one that has become smaller over time.

Rather than use networks from other fields as a benchmark, we can also compare the network of legal scholars against small-world networks simulated using algorithms designed to generate structures with small-world properties (significant clustering and low average path lengths). A Watts-Strogotz small-world graph is generated from a ring lattice structure in which each node is connected to the nearest nodes in the ring, and then proceeds by taking each edge connecting the node to its neighbor and randomly “rewiring” it to another node with some fixed probability. The resulting rewired network is a small world.

The average degrees in the 2010 legal scholars’ network and its giant component are 2.2 and 2.9, respectively. The average degrees in a small-world graph is an even number , so we cannot match the co-authorship graph precisely to a small-world graph with the same average degrees. As a result, I consider two possibilities. Table 3 compares the properties of the 2010 network and its giant component with connected small-world graphs for and The 2010 network has many fewer edges than the small world, so its density and average path length are lower, but the average and global clustering measures are much higher, confirming that the network of legal scholars had become a small world by the 2010s.

Table 3: Comparison to Watts-Strogotz Small-World Graphs

IV. Demographic and Institutional Trends

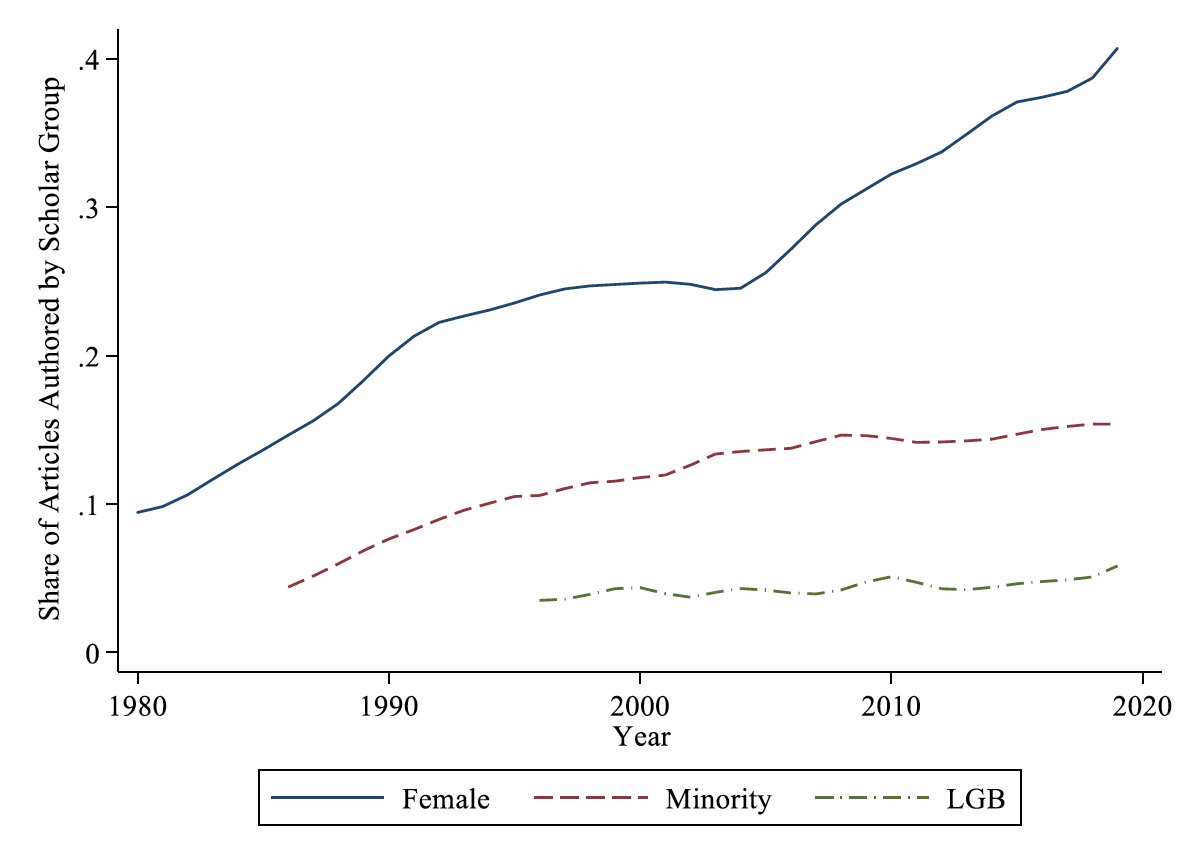

Not only has the network of legal scholars grown over time, but it has also diversified. The number and the share of female, minority, and LGB scholars has increased along with the increase in the overall numbers of active legal scholars, although the trends in representation across these groups differ. Consider first self-identified minorities. In the 1980s, 4.7% of scholars were minorities, and in the 1990s, the share of minority scholars doubled to 9.5%. But the increase in minority representation since then has been more modest, with 11.7% of active scholars reporting being minorities in the 2010s. The share of active self-identified LGB legal scholars was 1.8% in the 1980s and has increased each decade until reaching 3.9% in the 2010s. Finally, the number of female scholars has increased from 17.0% in the 1980s to 34.5% in the 2010s.

The growing number of female, minority, and LGB scholars in academia overall is reflected in the authorship of legal scholarship. Figure 10 shows that the share of articles authored by female, minority and LGB scholars has increased over time. Each line shows the trends in authorship by one group, smoothing out annual fluctuations to reveal the overall trend.

Figure 10: Share of Articles with Female, Minority or LGB Authorship

Comparing across decades, in the 1980s, minorities authored 4.3% of articles, and in the 2010s, they authored 12.9% of articles. The share of articles authored by LGB scholars was 1.8% in the 1980s and 4.2% in the 2010s. Women scholars authored 13.2% of articles in the 1980s and 32.9% in the 2010s. Comparing the representation of minorities, women, and LGB scholars as a share of scholars and in terms of their share of scholarship shows that minority and LGB scholars generate a modestly larger share of scholarship (12.9% and 4.2%) than their proportion of scholars (11.7% and 3.9%) while women scholars generate a modestly smaller percentage of legal scholarship (32.9%) than their proportion of scholars.

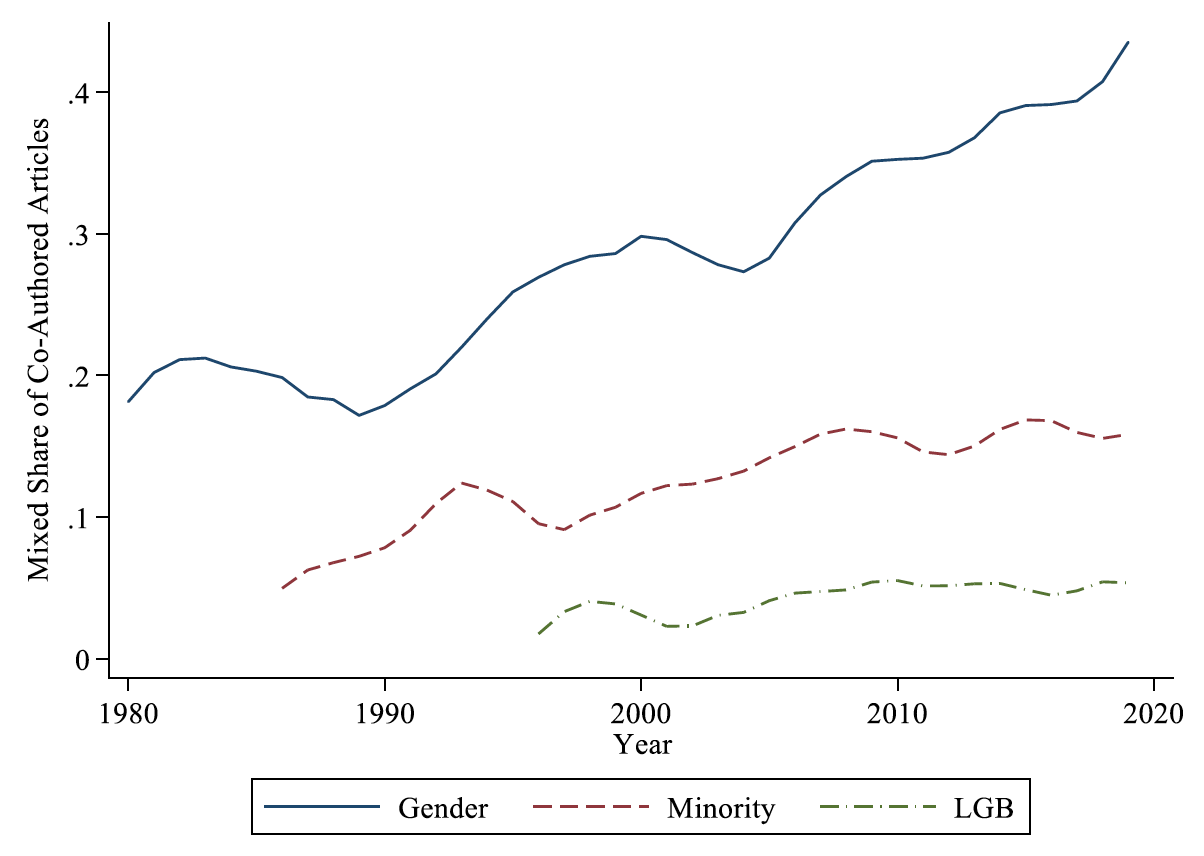

Although the law professoriate and legal scholarship now has more diverse representation, has it become more integrated? Or are minority, LGB, and women scholars cloistered in terms of their scholarly work? Figure 11 shows how the share of co-authored articles with “mixed” co-authorship (i.e., one minority and one non-minority, one LGB scholar and one non-LGB scholar, or one male and one female scholar) has evolved over time. As with Figure 10, the raw data have been smoothed to better see the trend lines.

The data show that the share of mixed co-authored articles has increased in line with the overall increase in female, minority and LGB scholars. Not only is an increasing share of legal scholarship co-authored, but an increasing share of co-authored scholarship reflects diversity along racial, gender, and LGB lines. This trend appears to be starkest for women scholars, who were represented on over 40% of co-authored scholarship by 2019, more than double their representation in 1980. The increase in women’s representation began its steep ascent around 1990 and continued until the end of the sample period.

Figure 11: Share of Co-Authored Articles with Mixed Co-Authorship

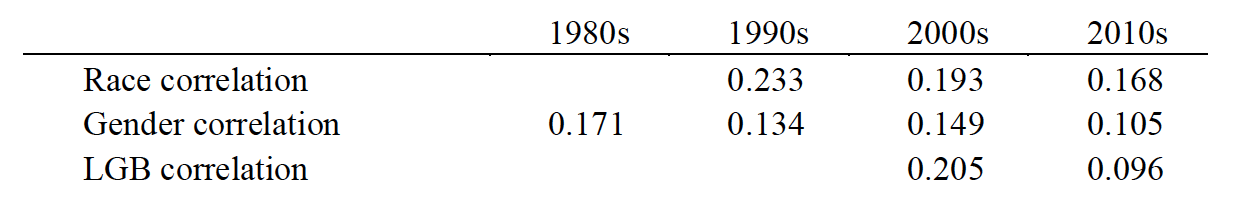

The increase in mixed co-authorship over time does not, however, imply that co-authorship relationships are formed without regard to differences in race, gender, or sexual orientation. Members of the same gender or minority group could still be more likely to co-author because of scholarly or personal affinities or geographic clustering in the same region or at the same law school. On the other hand, members of different genders or minority statuses may be more likely to co-author because their differences are complementary and allow them to generate new ideas and make novel contributions. The differential probability for co-authorship links to form between nodes with the same attributes is known as homophily. To measure homophily by minority, gender, and sexual minority status, Table 4 reports the assortativity coefficient for each characteristic and decade for which I have mostly comprehensive data on the characteristic. This measure has a value of 0 when there is no sorting by the attribute. A positive value is evidence of homophily—scholars co-authoring with scholars of the same “type”—while a negative value is evidence that similar scholars are less likely to co-author.

Table 4: Homophily by Attribute

For each decade and each demographic category, the coefficient is positive, indicating that legal scholars have some affinity to co-author with scholars who are of the same gender and minority status. But also, for gender, minority status, and LGB status, the strength of that homophily is declining over time. Thus, not only is legal academia becoming more diverse over time, but it is also becoming less segregated, at least in terms of scholarly collaboration. This is good news, because it increases the likelihood that the fruits of the scholarly network—information sharing and scholarly visibility for professional advancement—are more widely shared than they would be in a more segregated network.

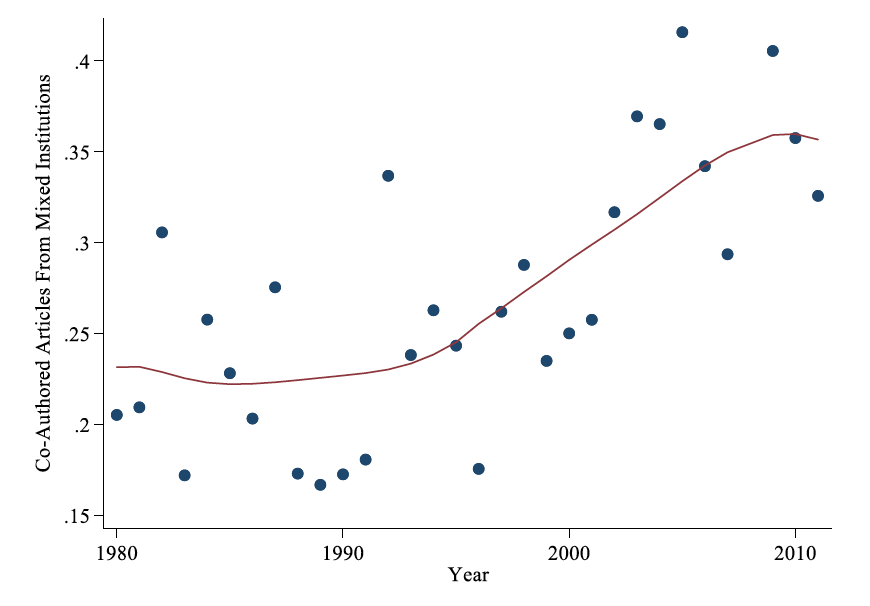

One other aspect of scholarly segregation is the amount of co-authorship that happens between scholars at different institutions. Although technological developments make it easier to collaborate with scholars from other institutions than before by reducing the costs of communication,43 43.See, e.g., Mu‐Hsuan Huang, Ling‐Ling Wu & Yi‐Chen Wu, A Study of Research Collaboration in the Pre‐web and Post‐web Stages: A Coauthorship Analysis of the Information Systems Discipline, 66 J. Ass’n for Info. Sci. & Tech. 778 (2015).Show More co-authorship networks may remain institutionally fragmented. And fragmentation reduces the information flow across institutions, thereby erecting barriers toward the mobility of law professors and the likelihood of fruitful intellectual collaborations. Moreover, co-authorship across law schools may usefully undermine “letterhead bias,” the idea that opportunities for scholarly publication depend on the perceived status of the author.

Figure 12 shows that the fraction of all co-authored articles with authors from different law schools has increased over time. Although the data series exhibits a lot of volatility, it also has a clear upward trend. The dots plot the raw data, and the solid line is a smoothed line to better illustrate the trend. The data series ends in 2011, which is the last year for which electronic access to the AALS directory and its information on faculty affiliation was available.

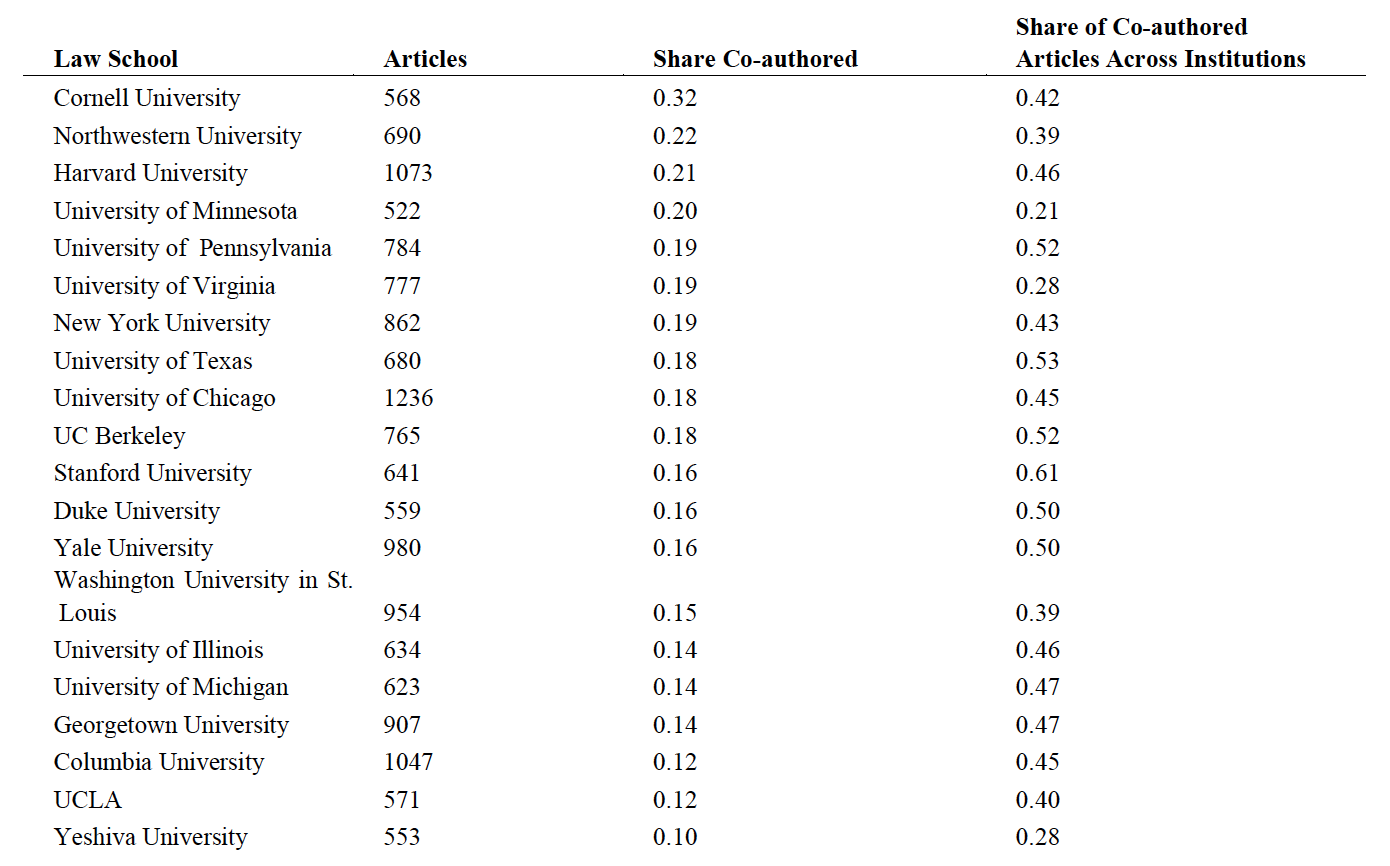

There is also considerable variation among law schools in how much their faculty co-author and whether those co-authorship relationships cross institutional boundaries or are within-school. Table 5, in the Appendix, lists the top 10 percent of law schools in terms of published articles from 1980–2019. Scholars from Cornell and Northwestern were most likely to co-author during this period, a fact which may be attributable to those faculties’ strength in and emphasis on interdisciplinary work. Among co-authored papers, scholars from Stanford, Texas, and UPenn are represented more than scholars from other institutions.

Figure 12: Co-authored Articles with Authors from Different Law Schools

V. Author Name Ordering

The rise of co-authorship and the diversification of legal academia raises several questions about how scholars are credited for co-authored work. The answers to these questions feed directly into scholars’ prospects for promotion, tenure, and compensation. And there is reason to worry that the allocation of credit may be biased. In economics, for example, there is evidence that co-authorship reduces the probability of tenure for junior female economists but not junior male economists.44 44.See Sarsons, supra note 17; Andrew Hussey, Sheena Murray & Wendy Stock, Gender, Coauthorship, and Academic Outcomes in Economics, 60 Econ. Inquiry 465 (2022).Show More Moreover, the penalty for co-authorship is greater when women co-author with men than when they co-author with other women.45 45.Sarsons, supra note 17.Show More One reason that co-authors may not receive equal credit for a joint publication is the order in which their names are listed on the article.46 46.Boris Maciejovsky, David V. Budescu & Dan Ariely, Research Note—The Researcher as a Consumer of Scientific Publications: How Do Name-Ordering Conventions Affect Inferences About Contribution Credits?, 28 Mktg. Sci. 589 (2008).Show More In some academic disciplines, the order of authors’ names is intended to convey their relative contributions to the work. Legal scholarship—like economics—typically but not exclusively uses alphabetic ordering. Nevertheless, the first-named author on a co-authored work may receive more credit than later authors because theirs may be the only name that appears when the work is cited by subsequent scholars.

In 2020, some student-edited law journals dispensed with the citation convention to identify only the first author by name for articles with more than two authors. The initiative to list all the authors was intended mostly to ensure that all scholars working on the piece receive credit, but also because the “et al.” convention may have disfavored junior, minority or female scholars if they are underrepresented among first authors. There is evidence of gender bias in the assignment of the first author position in other academic disciplines,47 47.Arturo Casadevall, Gregg L. Semenza, Sarah Jackson, Gordon Tomaselli & Rexford S. Ahima, Reducing Bias: Accounting for the Order of Co–first Authors, 129 J. Clinical Investigation 2167 (2019).Show More so perhaps this is true in law as well. In this section, I explore the representation of scholars in the first author position over the last 40 years.

For articles with more than two authors—those for which the “et al.” convention would be used—I calculated the share of first authors and the share of all authors who are women, minority, and sexual minority scholars. Comparing each group’s share of authors with their share of first authors will reveal the effect of doing away with the et al. convention on representation of these scholars’ names in citations. I then focused on articles with mixed authorship and calculated the share of these articles for which the woman or minority was the first author. To evaluate whether representation is meaningfully different among mixed author articles than one would expect if lead authorship were assigned randomly, I simulated random assignment of lead authorship among these articles 1000 times and calculated the expected share of female/minority lead authors and the probability of observing the actual share of female/minority lead authors.

Whereas 26.2% of all co-authors are women scholars, 24.5% of the first authors are women scholars. LGB scholars made up 2.7% of all authors and only 1.6% of all first authors. By contrast, racial minority scholars comprise 7.7% of all co-authors and 8.3% of all first authors. Thus, the et al. convention reduces the share of named scholars who are women and the share of LGB scholars and increases the share of named authors who are racial minorities.

Who occupies the first author position for articles with mixed co-authors? For women, the expected share of first authors based on random assignment is 44.1% and the actual share is 41.6%. The probability of observing female representation among first authors of 41.6% or less under the assumption of random assignment of author ordering is 0.12, a p-value that is suggestive but not generally associated with a rejection of the null hypothesis (of random assignment of author ordering). For LGB scholars, the expected share of first LGB lead authors among mixed articles is 43.7% but the actual share is 24.6%, a dramatically lower number associated with a p-value of close to 0. For racial minorities, the expected share of first authors based on random assignment is 39.7% and the actual share of minority first authors is 43.4%. Under a null hypothesis of random assignment, the probability of observing minority representation among first authors of 43.4% is 0.13, also suggestive but not strong evidence against the null.

Returning to our discussion at the outset about the reasons for co-authorship, there are many explanations for why minority scholars may be “overrepresented” among first authors and women and sexual minorities “underrepresented,” relative to their share of co-authors in general. One possibility is that author ordering reflects relative contributions. Another possibility is that gender, race, and LGB status are correlated with factors such as seniority or professional status among co-authors that influence the assignment of author ordering. Another possibility is that first authorship has a greater professional return for some scholars. If co-authors are altruistic, they may acquiesce to assigning first authorship to the scholar who will benefit the most. Of course, it need not be altruism. This outcome could also result from bargaining among co-authors as they work together to maximize the aggregate boost to their professional reputations. In that case, the other scholars may extract concessions from the first author in the form of greater or more menial contributions to the project in exchange for the benefit of being first author.

VI. Discussion

The network of legal scholars looks dramatically different now than it did forty years ago. There were 63% more scholars publishing and 86% more articles written in the 2010s than the 1980s. The explosion in co-authorship in the last two decades has created a connected network of scholars to which more than 50% of legal scholars belong. As a result, even as the number of legal scholars has grown, their world is smaller than ever, a conclusion that is further supported by the increasing number of collaborations between scholars from different institutions.

As new scholars join the network, their attachment is not random. Certain scholars co-author much more than others, and some scholars tend not to co-author at all. And legal scholars tend to co-author with others of the same gender and minority status, although this correlation has declined over time. As the number of women, minorities, and LGB scholars has increased over time, the increase in representation is most dramatic for women both overall and in terms of participating in mixed co-authorship arrangements. When legal scholars do co-author, their names are listed alphabetically 65% of the time. Racial minority scholars are listed as first authors more frequently—and women and LGB scholars are listed as first authors less frequently—than one would expect based on their proportion in the population of authors. Future work should explore in greater depth how new scholars become incorporated into the network, what other factors help establish co-authorship relationships, and what the consequences of these relationships are for legal scholarship and the distribution of professional opportunities in legal academia.

Appendix

Table 1: Law Reviews in Sample

Table 2: Top Scholars by Number of Scholar Co-authors

Table 3: Top Scholars by Closeness Centrality

Table 4: Top Scholars by Betweenness Centrality

Table 5: Co-authorship by School

- See infra Figure 1. ↑

- See infra Part I. ↑

- Lorenzo Ductor, Sanjeev Goyal & Anja Prummer, Gender and Collaboration, Rev. Econ. & Statistics 24–25 (2021), https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_01113 [https://perma.cc/PS4Z-KXAK]. ↑

- In some cases, law school texts are based on methodological approaches that have been developed as legal scholarship. See, e.g., Robert Cooter & Thomas Ulen, Introduction to Law and Economics (5th ed. 2007). ↑

- Tracey E. George & Chris Guthrie, Joining Forces: The Role of Collaboration in the Development of Legal Thought, 52 J. Legal Educ. 559, 561–568 (2002); Michael I. Meyerson, Law School Culture and the Lost Art of Collaboration: Why Don’t Law Professors Play Well with Others?, 93 Neb. L. Rev. 547, 548–549 (2014). ↑

- Tom Ginsburg & Thomas J. Miles, Empiricism and the Rising Incidence of Coauthorship in Law, 2011 U. Ill. L. Rev. 1785, 1800–1812 (2011). ↑

- Paul H. Edelman & Tracey E. George, Six Degrees of Cass Sunstein, 11 Green Bag 2d 19, 22–31 (2007). ↑

- Id. at 27–30. ↑

- See, e.g., Daniel Martin Katz, Joshua R. Gubler, Jon Zelner, Michael J. Bommarito II, Eric Provins, & Eitan Ingall, Reproduction of Hierarchy? A Social Network Analysis of the American Law Professoriate, 61 J. Legal Educ. 76 (2011) (discussing the network of legal scholars and its impact on legal developments); Milan Markovic, The Law Professor Pipeline, 92 Temp. L. Rev. 813 (2019) (exploring how professors’ intellectual and social networks relate to the advancement of their careers); Keerthana Nunna, W. Nicholson Price II & Jonathan Tietz, Hierarchy, Race & Gender in Legal Scholarly Networks, 75 Stan. L. Rev. (forthcoming 2023) (analyzing how hierarchy, race, and gender affect the acknowledgment sections of law review articles). ↑

- See infra Part IV. ↑

- “LGB” is used instead of “LGBT” because the American Association of Law Schools (AALS) Directory of Law Teachers does not include data on transgender faculty. ↑

- Nunna et al., supra note 9. ↑

- Id. at 46. ↑

- On the importance of networks in job matching, see Yannis M. Ioannides & Linda Datcher Loury, Job Information Networks, Neighborhood Effects, and Inequality, 42 J. Econ. Literature 1056, 1061–1062 (2004). ↑

- Ginsburg & Miles, supra note 6, at 1788–90, 1794. For a theoretical model of the co-authorship choice, see Bruna Bruno, Economics of Co-authorship, 44 Econ. Analysis & Pol’y 212 (2014). ↑

- Id. ↑

- Heather Sarsons, Recognition for Group Work: Gender Differences in Academia, 107 Am. Econ. Rev. 141, 144 (2017). ↑

- Ginsburg & Miles, supra note 6, at 1790–93. ↑

- Matthew O. Jackson, Social and Economic Networks 20 (2010). ↑

- Id. at 32. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at 26. ↑

- Id. at 32. ↑

- Id. at 33. ↑

- Id. at 29. ↑

- Mark E.J. Newman, Mixing Patterns in Networks, 67 Physical Rev. 2 (2003). ↑

- Jackson, supra note 18, at 35. ↑

- Id. ↑

- For racial minorities, I used lists published in the 1986, 1989, 1990, 1991, 1992, 1996, 2000, 2004, 2007, 2011, 2014, and 2019 editions. For sexual minorities, I used lists from the same years, beginning in 1996. ↑

- Ginsburg & Miles, supra note 6, at 1785. ↑

- Id. at 1785 (“[R]esults support the view that specialization, and specifically the growth of empirical scholarship, has contributed to the trend of coauthorship in legal academia.”). ↑

- Mark C. Suchman & Elizabeth Mertz, Toward a New Legal Empiricism: Empirical Legal Studies and New Legal Realism, 6 Ann. Rev. L. & Soc. Sci. 555, 556 (2010) (“Since the mid-1990s, several groups of scholars have championed a renewed dialog between law and social science.”). ↑

- Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, Wiley Online Libr., https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/loi/17401461 [https://perma.cc/6GXQ-LCEK] (last visited Oct. 28, 2022). ↑

- See Ginsburg and Miles, supra note 6, at 1785 (“Coauthored articles were far more common in . . . [the Journal of Legal Studies and Journal of Law, Economics and Organization] . . . than in the general interest, student-edited law reviews.”). ↑

- For details about the calculation of these centrality measures, see Jackson, supra note 19, at 39. ↑

- The data come from Jackson, supra note 19. ↑

- Meyerson, supra note 5, at 548. ↑

- Andy H. Barnett, Richard W. Ault & David L. Kaserman, The Rising Incidence of Co-Authorship in Economics: Further Evidence, Rev. of Econ. & Stat. 539 (1988). ↑

- Specifically, the average shortest path should be of the same order as . ↑

- In this I follow Sanjeev Goyal, Marco J. van der Leij & José Luis Moraga‐González, Economics: An Emerging Small World, 114 J. Pol. Econ. 403 (2006). Goyal et al. builds on the seminal analysis of Duncan J. Watts & Steven H. Strogatz, Collective dynamics of ‘small-world’ networks, 393 Nature 440 (1998). ↑

- Goyal et al., supra note 39, at 408. ↑

- Id. at 405. ↑

- See, e.g., Mu‐Hsuan Huang, Ling‐Ling Wu & Yi‐Chen Wu, A Study of Research Collaboration in the Pre‐web and Post‐web Stages: A Coauthorship Analysis of the Information Systems Discipline, 66 J. Ass’n for Info. Sci. & Tech. 778 (2015). ↑

- See Sarsons, supra note 17; Andrew Hussey, Sheena Murray & Wendy Stock, Gender, Coauthorship, and Academic Outcomes in Economics, 60 Econ. Inquiry 465 (2022). ↑

- Sarsons, supra note 17. ↑

- Boris Maciejovsky, David V. Budescu & Dan Ariely, Research Note—The Researcher as a Consumer of Scientific Publications: How Do Name-Ordering Conventions Affect Inferences About Contribution Credits?, 28 Mktg. Sci. 589 (2008). ↑

-

Arturo Casadevall, Gregg L. Semenza, Sarah Jackson, Gordon Tomaselli & Rexford S. Ahima, Reducing Bias: Accounting for the Order of Co–first Authors, 129 J. Clinical Investigation 2167 (2019). ↑

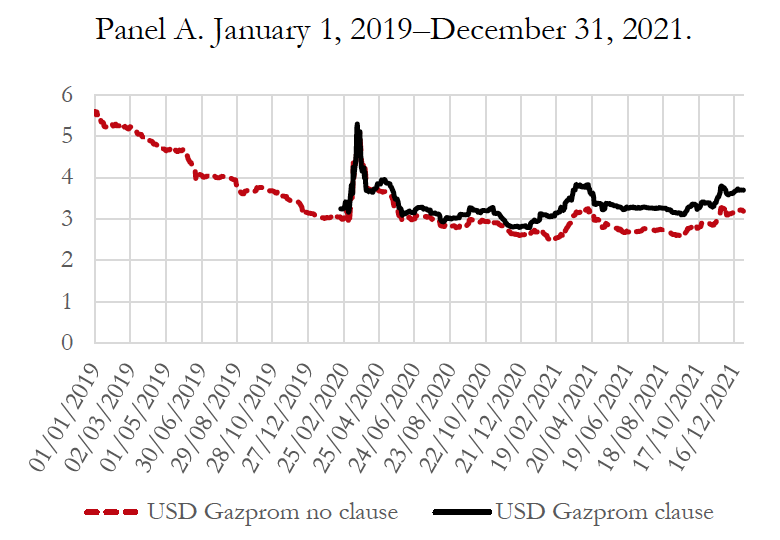

Panel A. January 1, 2019–December 31, 2021.

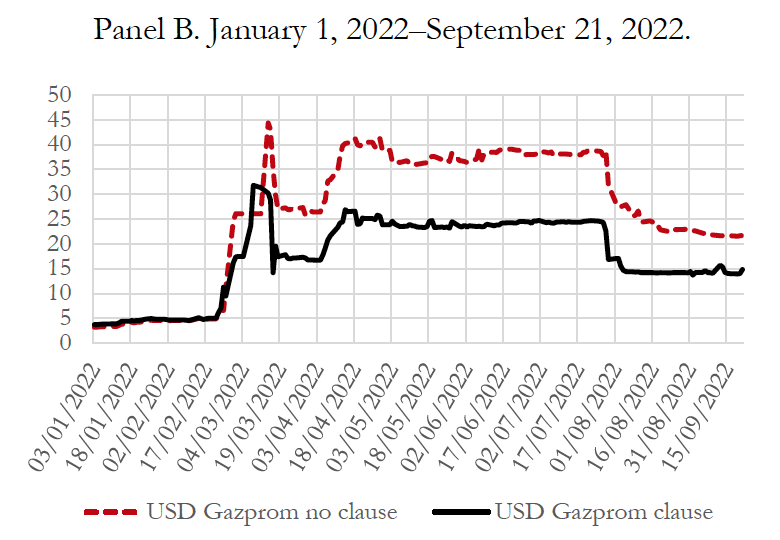

Panel A. January 1, 2019–December 31, 2021. Panel B. January 1, 2022–September 21, 2022.

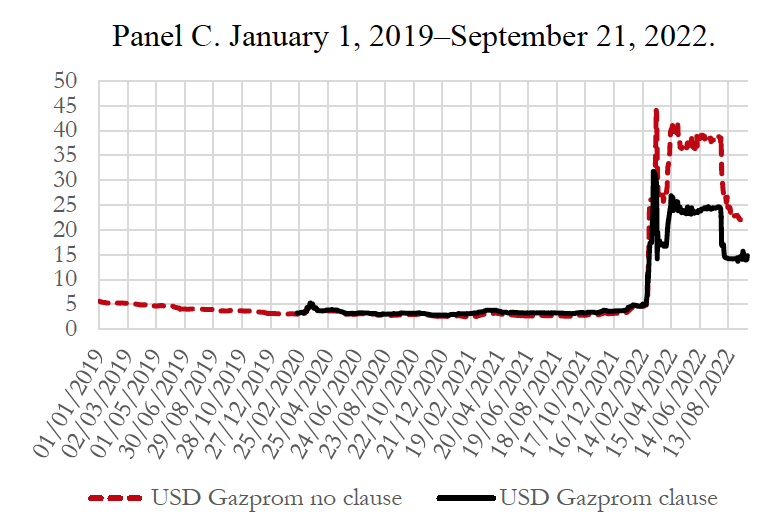

Panel B. January 1, 2022–September 21, 2022. Panel C. January 1, 2019–September 21, 2022.

Panel C. January 1, 2019–September 21, 2022. Panel A. January 1, 2019–December 31, 2021.

Panel A. January 1, 2019–December 31, 2021. Panel B. January 1, 2022–September 21, 2022.

Panel B. January 1, 2022–September 21, 2022. Panel C. January 1, 2019–September 21, 2022.

Panel C. January 1, 2019–September 21, 2022.